- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

PROTOCOL: Evidence and Gap Map Protocol: Interventions promoting safe water, sanitation, and hygiene for households, communities, schools, and health facilities in low‐ and middle‐income countries

research-article

Read this article at

There is no author summary for this article yet. Authors can add summaries to their articles on ScienceOpen to make them more accessible to a non-specialist audience.

Abstract

Background

The problem

According to the Joint Monitoring Programme (JMP), an estimated 844 million people

do not use improved water sources and 2.3 billion lack access to even a basic sanitation

service (WHO/UNICEF JMP, 2017). Worldwide, 892 million people still practice open

defecation. Rural, poor and, vulnerable households have particularly limited access

to adequate facilities and inequities are often regionally focused. Populations in

sub‐Saharan Africa and Oceania are lagging behind in access to improved drinking water

sources, whilst South Asia and sub‐Saharan Africa have the highest concentrations

of open defecation.

Limited, or no, access to safe facilities for eliminating human waste, gathering clean

drinking water, or practicing hygienic washing and food preparation practices exposes

individuals to higher‐levels of contagious pathogens. There is evidence to suggest

that poor water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) conditions are associated with high

levels of diarrhoeal disease (Clasen et al., 2015; De Buck et al., 2017), respiratory

infections (Aiello et al., 2008), parasitic worm (e.g. helminth and schistosome) infections

(Ziegelbauer et al., 2012), trachoma (Rabiu et al. 2012), and possibly even tropical

enteropathy (Cumming and Cairncross, 2016). Chronic high infection rates are among

the leading causes of undernutrition and death in children (Cairncross et al. 2014).

Diarrhoeal diseases, in particular, are the second most common cause of death for

children under the age of five; diarrhoeal diseases, in particular, are estimated

to kill 480,000 children a year (UNICEF, 2018). Beyond the health consequences, poor

quality WASH conditions may also lead to long‐term adverse social and economic outcomes

including diminished educational attainment (Hennegan et al., 2016), due to both children's

school enrolment and attendance as well as teacher attendance, and implications for

employment, life‐time wage earnings and income (Hutton et al., 2007; Turley et al.

2013).

Inadequate access affects disadvantaged groups disproportionately, but women and girls

are particularly badly affected by the costs of having limited access to WASH facilities.

They often carry the majority of the burden associated with collecting water (including

time, calories spent, musculoskeletal injuries, risks of assault and attack by humans

and wild animals, and road casualties), and can be placed in high‐risk situations

when using unsafe places to defecate (Cairncross and Valdmanis, 2006; Cairncross et

al., 2010; Sorenson et al., 2011; Sahoo et al., 2015). Women and adolescent girls

also experience particular hardships where inadequate WASH facilities constrain menstrual

hygiene management (Hennegan et al., 2016; Sumpter and Torondel 2013). There may also

be adverse maternal and child health implications due to inadequate WASH services

in health facilities and other places of newborn delivery (Benova et al., 2014).

In 2015, more than 150 world leaders adopted the new 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development,

which sets new goals for 2030 that build upon, and go even further, than the Millennium

Development Goals (MDGs). Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 6 aims to ‘ensure the

availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all’ by 2030 (UN

Water, 2018). In order to help achieve these universal targets, which includes reaching

the most disadvantaged populations, decision makers need access to high quality evidence

on what works in WASH promotion in different contexts, and for different groups of

people. Both impact evaluations and evidence syntheses can be useful to decision makers.

Single impact studies are useful for providing information on how a programme functions

in a specific context; for example, the recent WASH‐Benefits trials were unable to

detect effects of combined or single water, sanitation, or hygiene interventions on

child linear growth in Bangladesh and Kenya (Luby et al., 2018; Null et al., 2018).

However, there has been criticism of the generalisability of the studies and the interventions

provided (Cumming and Curtis, 2018; Coffey and Spears, 2018). On the other hand, high

quality systematic reviews critically appraise and corroborate the findings from individual

studies, as well as providing a steer to decision makers about which findings are

generalisable and which are more context‐specific (Waddington et al., 2012).

For policymakers, practitioners and commissioners of research to make informed decisions,

they need to be able to identify where high quality evidence exists in usable formats,

and where more evidence is needed. There are also concerns about approaches used to

measure outcomes in WASH sector primary research, such as self‐ and carer‐reporting

of diarrhoeal disease (e.g. Schmidt and Cairncross, 2009). These concerns necessitate,

firstly, examining the critically appraised evidence (from systematic reviews) and,

secondly, evidence on a wide range of behavioural, health and socio‐economic outcomes.

What remains an issue, therefore, is the extent of evidence on the effectiveness of

interventions to improve access to WASH services for households, communities, schools

and health facilities on outcomes in the round, and an assessment of what primary

and synthesised evidence is still needed across different low‐ and middle‐income countries

and regions.

Scope of the evidence and gap map

Water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) interventions have two important components to

them – the ‘what’ and the ‘how’. The ‘what’ describes the technology that the participants

end up with (for example, a latrine) and the ‘how’ describes the mechanism of the

intervention (for example, whether toilets are provided on a subsidised basis or at

full cost with some form of social marketing). Prior to the early‐2000s, the focus

of the conversation was principally on ‘what’ works; research was centred on understanding

and demonstrating the short and long term consequences of providing a technology.

However, over the last 15 years the conversation has increasingly switched from not

just what technology to provide but what is the best way to both get it into the community

and have it be regularly used. This has seen the rise of behaviour change and systems‐based

approaches. Due to this changing focus, the principal interventions will be defined

by the mechanisms (the ‘how’); this means that the evidence gap map will present intervention

mechanisms against outcomes. There will then be a filter for the technology provided

by the intervention; this will allow for easy comparison of the evidence for different

mechanisms of providing, for example, latrines.

Mechanisms for providing WASH technologies can be classified into four main groups;

direct provision, health messaging, psychosocial ‘triggering’, and systems‐based interventions.

The below definitions have been adapted from relevant literature in the field (De

Buck et al., 2017 and Poulos et al., 2006):

Direct provision mechanisms cover all interventions where hardware (such as a latrine

or water purifier) is provided for free and has been chosen by an external authority

(such as a non‐governmental organization).

Health messaging, most often focused on sanitation or hygiene, is typically a directive

educational approach designed to help individuals, or communities, improve their health

through increasing their knowledge and/or skills.

Psychosocial ‘triggering’ falls into two subcategories of directive and participative

approaches. Both subcategories use behavioural factors which have been derived from

psychosocial theories (such as emotions, like disgust and the desire to be a good

parent, or social pressure) to motivate behaviour change, rather than reason. An example

of this approach is community‐led total sanitation (CLTS) where the community is encouraged

to discuss how they would like sanitation practices to change, identify problem areas

(e.g. ‘walks of shame’), and use social cohesion and pressure to motivate people to

construct latrines and stop practicing open defecation (Kar and Chambers, 2008).

Systems‐based mechanisms try to change people's behaviour by changing the wider system

around them. These approaches include pricing reform, improving operator performance,

private sector (PS) and small‐scale independent provider (SSIP) participation, and

community driven development (CDD).

The behavioural change communication (BCC) approaches – health messaging and psychosocial

‘triggering’ – are often combined with both direct provision and systems‐based approaches

in an attempt to simultaneously overcome the social and financial barriers to accessing

appropriate WASH services.

WASH technologies for household and personal consumption can be classified into four

main, related, groups: water quantity, water quality, sanitation hardware and sanitation

software (hygiene) (Esrey et al., 1991):

Water quantity technologies provide a water supply or distribution system. Water may

be supplied to communities at source, such as through a public standpipe, or at point‐of‐use

(POU), such as being piped directly to households.

Water quality technologies provide the means to protect water from, or treat water

to remove, microbial contaminants. Examples of water treatment technologies include

filtration, chlorination, flocculation, solar disinfection, boiling, and pasteurising.

Water quality improvements are most commonly undertaken in the household, rather than

at the source, though this class of interventions also includes treatment at source

and provision of containers for safe transportation and storage of water.

Sanitation technologies provide means to dispose of excreta (such as faeces), through

new or improved latrines or connection of existing latrines to the public sewer.

Hygiene technologies consist of hygienic practices, and facilitators of these such

as soap, hand sanitisers, and washing stations. Hygiene practices are most often focused

on handwashing but can also include food hygiene, such as proper food storage and

washing dishes appropriately, as well as wearing appropriate footwear, or menstrual

hygiene management.

A third important dimension to any intervention is how, or where, participants interact

with it in terms of both their social and physical environments. Interventions that

seem similar can be very different in nature, and their outcomes not necessarily comparable,

due to the space they inhabit. An ecological model can be integrated into the types

of technology to reflect where a technology is used. The place of use is important

in the WASH sector as it affects the convenience to users, and therefore adoption

rates, as well as how the intervention disrupts the causal chain of disease transmission.

The four main spaces in which WASH technologies are provided are in the home (for

use by an individual household only), in the community (to be shared), at a school,

and at a health facility.

Multiple mechanisms can be used in one programme; for example, soap could be directly

provided with a social marketing campaign on handwashing. Multiple WASH technologies

are also often be provided together in programmes where they are combined. A common

example is combined water supply and sanitation (WSS) programmes.

The quality of water supply, sanitation and hygiene facilities – that is, the extent

to which they are likely to provide potable drinking water or safe removal of excrement

from the human environment, or enable hygienic hand‐washing – is dependent on the

type of water or sanitation facility. Table 1 lists types of improved and unimproved

water, sanitation and hygiene facilities according to WHO/UNICEF JMP (2017).

Table 1

JMP classification of water, sanitation and hygiene facilities

Drinking water

Sanitation

Hygiene

Improved facilities

Piped supplies:

Tap water in the dwelling, yard, or plot

Public standposts/pipes

Non‐piped supplies:

Boreholes / tubewells

Protected wells and springs

Rainwater

Packaged water, including bottled water and sachet water

Delivered water, including trucks and small carts

Improved sources that require less than 30 minutes round‐trip to collect are defined

as ‘basic water’. Improved sources requiring more than 30 minutes are defined ‘limited

water’.

Networked sanitation:

Flush and pour flush toilets connected to sewers

On‐site sanitation:

Flush or pour flush toilets connected to septic tanks or pits

Pit latrines with slabs

Composting toilets, including twin pit latrines and container‐based systems

Shared facilities of the above types are defined as ‘limited sanitation’.

Fixed or mobile handwashing facilities with soap and water (defined as ‘basic hygiene’):

Handwashing facility defined as a sink with tap water, buckets with taps, tippy‐taps,

and jugs or basins designated for handwashing.

Soap includes bar soap, liquid soap, powder detergent, and soapy water.

Handwashing facilities without soap and water (e.g. ash, soil, sand or other handwashing

agent) are defined as ‘limited hygiene’

Unimproved facilities

Non‐piped supplies:

Unprotected wells and springs.

On‐site sanitation or shared facilities of the following types:

Pit latrines without slabs

Hanging latrines

Bucket latrines

No facilities

Surface water (e.g. drinking water directly from a river, pond, canal or stream)

Open defecation (disposal of human faeces in open spaces or with solid waste)

No handwashing facility on premises

Source: Based on WHO/UNICEF (2017).

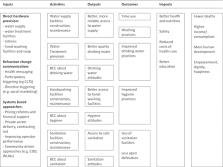

Conceptual framework of the EGM

The conceptual framework links WASH interventions with impacts along the causal chain

(Figure 1). Sector interventions – water and sanitation hardware and software provision

and interventions in sector governance (e.g. contracting out and subsidies) – are

presented to the left of the figure. Impacts on wellbeing – health, education, income

and empowerment – are presented on the right. The conceptual framework shows the causal

chain through which inputs are turned into final wellbeing impacts, through activities

(construction of new facilities or behaviour change campaigns), outputs (better access

to and quality of services) and outcomes (behaviour change, better use of those services).

Figure 1

WASH interventions conceptual framework

Source: authors based on White and Gunnarson (2008).

The links in the chain are not automatic. For example, in the particular case of water

quality, faecal contamination of drinking water between source and point‐of‐use (POU)

means that hygienic approaches may be needed to store clean water collected at source,

or treat water for contaminants in the household (POU). Better access to water supply

(quantity) may improve health by reducing contamination in the environment by enabling

better personal hygiene (e.g. handwashing) and environmental hygiene (e.g. safe disposal

of faeces). Factors such as environmental faecal contamination may prevent impacts

from clean drinking water provision being realised. Sustainability of impacts requires

continued (permanent) adoption and acceptance by beneficiaries as well as appropriate

solutions to reduce ‘slippage’ in improved behaviour and financial barriers to uptake

and technical solutions to ensure service delivery reliability. Scalability requires

that impacts which are demonstrated under ‘ideal settings’ of trials are achievable

in the context of ‘real world’ programme implementation, where beneficiaries may not

constantly be reminded to use technologies appropriately.

Why it is important to develop the EGM?

Progress towards the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) was uneven in the sector.

The MDG drinking water target to “halve the number without access to safe drinking

water (defined as access to water from an improved source within one kilometre of

the household)” was declared met in 2012, but of those who did gain improved access

to drinking water since 1990, supplies are mainly provided at the community level

and are often unreliable (WHO/UNICEF, 2013). The MDG sanitation target to “halve the

number without access to sanitation by 2015” was missed (UN, 2015).

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are aspirational, aiming for universal coverage

by 2030, and adding targets for hygiene.

1

The SDG targets are as follows (WHO/UNICEF JMP, 2017):

To provide safe and affordable drinking water for all, measured by population using

safely managed drinking water that is an improved drinking water source, located on

premises, available when needed and free from contamination (SDG 6.1).

To end open defaecation and provide adequate and equitable sanitation for all, measured

by population using safely managed sanitation services and a basic handwashing facility

with soap and water (SDG 6.2). Safely managed sanitation is defined as an improved

facility where excreta is treated and disposed of in situ or off‐site.

To ensure all men and women have access to basic services, including basic drinking

water, sanitation and hygiene (SDG 1.4).

In order to move towards these ambitious targets, it is likely that substantial improvements

in resource allocation will be needed to promote interventions which are effective

in improving behaviours and outcomes in particular contexts. The purpose of this evidence

gap map is to assist policy‐makers and practitioners in gaining access to evidence

on the effectiveness of WASH interventions.

In 2014, 3ie produced an evidence gap map (EGM) on the effectiveness of WASH interventions

in improving quality of life outcomes. That map includes evidence until February 2014

and only considered quality of life outcomes (health and non‐health) as primary outcomes.

Behaviour change outcomes were included as secondary outcomes, provided the study

also included primary outcomes. In addition, the map excluded interventions in health

facilities. This update aims to capture studies conducted since, as well as broadening

the included interventions and outcomes to better reflect the state of evidence on

WASH in 2018.

Existing evidence maps and relevant systematic reviews

In 2014, 3ie produced an evidence gap map for household and community interventions

for promoting water, sanitation, and hygiene consumption in LMICs.

2

The present study is an update of that map. We are updating the searches and the scope

of that map to incorporate: 1) behaviour change as a primary outcome; and 2) water,

sanitation and hygiene interventions based in health facilities to improve maternal

and child health. A large number of impact evaluations and systematic reviews of WASH

interventions will be incorporated in the map. For example, Table 2 lists some reviews

of interventions for water, sanitation and hygiene promotion in households and communities,

many published prior to 2014.

Table 2

Systematic reviews of WASH interventions

Outcomes

Systematic reviews

Diarrhea

Curtis & Cairncross 2003

Gundry et al. 2004

Fewtrell & Colford 2004 (also published as Fewtrell et al. 2005)

Arnold and Colford 2007

Clasen et al. 2007

Ejemot et al. 2008

Waddington et al. 2009

Hunter 2009

Clasen et al. 2010

Cairncross et al. 2010

Norman et al. 2010

Respiratory infections

Aiello et al. 2008

Rabie and Curtis 2006

Helminth infections

Ziegelbauer et al. 2012

Trachoma

Ejere et al. 2012

Arsenic contamination

Jones‐Hughes et al. 2013

Nutrition

Dangour et al. 2013

Education

Jasper et al. 2012

Birdthistle et al. 2011

Income

Turley et al. 2013

Attitudes and behaviour

Null et al. 2012

De Buck et al. 2017

Objectives

The overarching aim of the evidence map is to gather and present the rigorous empirical

research on the effectiveness of interventions to improve consumption of water, sanitation

and hygiene in the household, communities, schools and health facilities. This protocol

provides the project plan for an update to the 2014 WASH evidence gap map (EGM) to

take stock of the existing evidence, and capture newly published work, on the effects

of interventions in these areas.

The aim of the EGM is to identify, map, and describe existing evidence on the effects

of interventions to improve access to, and quality of, WASH infrastructure, services,

and practices in low‐ and middle‐income countries. This update of the original map

aims to capture additional studies conducted in the last three years and extend the

scope of the EGM, in particular to cover behavioural outcomes and WASH interventions

at healthcare facilities. The primary outcomes for this gap map include morbidities

(e.g. diarrhoea), mortality, psychosocial health, nutritional status, education, income,

and time use. In addition, behavioural outcomes will also be included as primary outcomes,

such as water treatment practices, hygiene behaviour, and latrine construction in

CLTS.

The update of the EGM addresses three objectives:

(1)

To identify existing evidence from high quality impact evaluations and systematic

reviews (SRs), particularly those published since 2014, which can be used to inform

policy.

(2)

To expand the scope of the EGM to better capture WASH behaviour change and programmes

implemented at healthcare facilities, with the aim of improving the map's policy relevance.

(3)

To identify existing gaps in evidence where new primary studies and systematic reviews

could add value.

The results from this EGM aim to inform the direction of future research surrounding

WASH, and discussions based on systematic evidence about which approaches and interventions

are most effective in the WASH sector, whether they are used in small scale projects

or large scaled‐up programmes.

Methodology

Defining evidence and gap maps

Evidence gap maps aim to establish what we know, and do not know, about the effectiveness

of interventions in a thematic area (Snilstveit et al., 2016).

3

The evidence gap map presented here includes evidence from primary studies and systematic

reviews. It provides a graphical display of interventions and outcomes, indicating

the density and paucity of available evidence, and gives confidence ratings for systematic

reviews. Evidence gap maps articulate absolute gaps, which are filled with new primary

studies, and synthesis gaps, which are filled with new systematic reviews and meta‐analyses.

They are global public goods which attempt to democratise high quality research evidence

for policy makers, practitioners, the public and research commissioners.

Table 3

Intervention mechanism classifications

Mechanism of delivery

Sub‐categories

Interventions

Direct provision

None

The provision of any WASH hardware for free and which has been chosen by an external

authority. This includes interventions where soap is handed out, water purifiers given

away, or latrines built by external actors.

Health messaging

None

Directive hygiene, and sometimes sanitation, education where participants are provided

with new knowledge or skills to improve their health. These information campaigns

may be provided by television, radio, or printed media; provided directly to specific

households or through sessions at community meetings / schools / etc.; or provided

directly to community leaders or health workers.

Psychosocial ‘triggering’

Directive

Psychosocial ‘triggering’ covers campaigns that use emotional and social cues, pressure,

or motivation to encourage community members to change behaviours. Directive mechanisms

are typically social marketing campaigns, which use commercial marketing techniques

to promote the adoption of beneficial behaviours.

Participatory

Participatory mechanisms are typically a community‐based approach and promote behaviour

change through consultation with the community, a two‐way dialogue, and joint‐decision

making. Community‐led total sanitation (CLTS) is the most common intervention with

this mechanism.

Systems‐based approaches

Pricing reform

This covers all interventions that aim to change behaviour, such as the use of a technology,

through changing the price of the requisite hardware. This includes subsidies and

vouchers aimed at consumers.

Improving operator performance

These interventions improve access to WASH facilities and services by improving the

functioning of the current service provider. This includes improving accountability,

increasing oversight/regulation, and changing the financing structure.

Private sector (PS) and small‐scale independent providers (SSIPs) involvement

These interventions encourage the private sector, including not for profits, to become

the providers of WASH facilities and services on a commercial basis.

Community driven development (CDD)

CDD is a form of decentralised delivery that focuses on putting the community at the

centre of the planning, design, implementation, and operations of their service provider.

It typically uses a participatory approach, cost sharing, and often a component of

local institutional strengthening. It includes social funds.

Multiple mechanisms

Direct provision with health messaging

These interventions combine the direct provision of hardware with an intensive health

messaging campaign. If only a single session is provided to explain the new hardware,

this would simply appear under “direct hardware provision”.

Direct provision with psychosocial ‘triggering’

These interventions combine the direct provision of hardware with behavioural change

communication that uses psychosocial triggers; these can be either participatory or

more often directive (e.g. a social a marketing campaign).

Systems‐based approaches with health messaging

These interventions combine systems‐based approaches (e.g. subsidies) with health

messaging.

Systems‐based approaches with psychosocial ‘triggering’

These interventions combine systems‐based approaches with behavioural change communication

that uses psychosocial triggers.

The framework

The framework for this evidence map (Appendix A) is based on the previous WASH evidence

map framework developed by the authors (see footnote 2). However, the framework was

updated based on a review of the academic and policy literature, and in consultation

with relevant decision makers and other key stakeholders (see stakeholder engagement

below). The included systematic reviews and impact evaluations will be identified

through a comprehensive search of published and unpublished literature. It will include

both completed and on‐going studies to help identify research in development that

might help fill existing evidence gaps.

The finalised updated evidence map will be structured around a framework of policy

relevant WASH mechanisms and outcomes, with a filter for technologies, and will be

available online at 3ie's evidence gap map portal.

4

Key features include:

Table 4

Intervention technology classifications

WASH technologies

Sub‐categories

Interventions

Water Supply

Source

New or improved water supply or distribution methods that do not provide the water

directly to households. This includes boreholes or standpipes that require travel

for water collection.

Point of use (POU)

New or improved water supply or distribution methods that provide water directly to

the household or at a communal point that requires no travel (i.e. in a garden shared

by 20 houses). This includes water directly piped to houses or standpipes within the

near vicinity.

Water Quality

Source

Supplies for, and information on, wither water treatments to remove microbial contaminants

or safe water storage practices at a communal water access point.

POU

Supplies for, and information on, water treatments to either remove microbial contaminants

or safe water storage practices within the household or commune.

Sanitation hardware

Latrines

New or improved hardware for latrines or other means of excreta disposal.

Sewer connection / drainage system

Connecting existing means of excreta disposal to a sewer or other drainage system.

Hygiene

Soap or hand sanitiser

Soap or similar products (e.g. hand sanitiser) with information on how to properly

use them.

Other hygiene supplies

Toilet paper, sanitary towels, or other hygiene products with information on how to

correctly use them.

Improved handwashing practices

Knowledge on the best practices for handwashing.

Other improved hygiene practices

Knowledge on the best practices for other hygiene techniques or procedures (including

face washing, menstrual hygiene, and latrine cleaning). This category also includes

personal food hygiene practices beyond handwashing at appropriate times. This includes

covering and storing food properly and washing dishes effectively.

Multiple WASH

Combined water supply and sanitation (WSS) programmes

Programmes that provide water supply and sanitation technologies.

Other combinations

All other programmes that provide multiple technologies.

The evidence map will highlight the best available evidence from systematic reviews

and provide access to user‐friendly summaries and appraisals of those studies.

The evidence map will also show where completed and, through the inclusion of trial

registries, on‐going primary studies (impact evaluations) have been conducted.

The evidence map will highlight absolute gaps in evidence (lack of studies for particular

interventions and/or outcomes).

The evidence map will highlight synthesis gaps where there are sufficient studies

for a new systematic review or an update of an existing systematic review.

The evidence map will have filters to highlight the evidence in particular countries

and regions, targeted at particular populations, using specific methodologies, and

specific intervention approaches.

Population

We will include any study populations regardless of age, sex or socio‐economic status.

However, populations are restricted to those in low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMICs),

as defined by the World Bank, at the time the research was carried out.

Intervention

Water, sanitation, and hygiene can be categorised into groups and sub‐groups of related

intervention mechanisms as shown in Table 3 (De Buck et al., 2017 and Poulos et al.,

2006). We have aimed to define our mechanism categories so that all common WASH programmes

would be eligible based on mechanism.

We then propose that the interventions should be further classified into groups and

sub‐groups of related WASH technologies as shown in Table 4 (Esrey, 1991; Fewtrell

et al., 2005; Waddington et al., 2009). We have aimed to define our technologies so

that all common personal and household WASH interventions would be eligible based

on technology.

As mentioned before, we will also be integrating an ecological model focused on where

a technology is physically used. Ecological models stress the importance of the dynamic

relationships between the personal and environmental factors that shape an individual's

behaviours and lifelong human development. They, and their socio‐ecological counterparts,

are often applied in crime prevention (for an example see Wortley, 2014) to explain

why changes in city planning and the physical space of a neighbourhood can affect

crime rates. Here we will separate out the hardware by place of use to emphasise the

differential effect, and potentially different theories of change, of providing the

same technology in different locations. The place of use affects both the convenience

of the technology, and therefore why and how much it is adopted, as well as how it

is expected to disrupt the transmission of disease. For example, providing a latrine

to a household is a very different intervention to providing one at a school or a

shared one to a community. The four main spaces in which WASH technologies for personal

consumption are provided are within a home (for the use of a single household), within

a shared community space (for example, a public water source such as a communal tubewell),

at a school, and at a health facility,

There are different combinations and ways of presenting evidence from both multiple

mechanisms and technologies, which we will consider further during the data extraction

phase.

We will exclude all studies without a clearly defined WASH intervention. Programmes

that combined a WASH intervention with a non‐WASH one will be included if the WASH

component is defined as a primary, not secondary, element.

Outcomes

We will include studies that report the following types of quality of life outcomes:

(1)

Health impacts including, but not necessarily limited to:

a.

diarrhoeal disease

b.

acute respiratory infections (ARIs)

c.

other water related infections such as helminths

d.

pain and musculoskeletal disorders

e.

psychosocial health and safety

f.

reproductive health outcomes

g.

mortality.

(2)

Nutritional impacts including, but may not be limited to:

a.

measures of stunting (e.g. height‐for‐age Z‐scores, HAZ)

b.

wasting (e.g. weight‐for‐height Z‐scores, WHZ, and body mass index, BMI)

c.

underweight (e.g. weight‐for‐age Z‐scores, WAZ).

(3)

Social and economic impacts, for example:

a.

educational outcomes (e.g. absenteeism)

b.

time use

c.

labour market outcomes (e.g. employment and wage)

d.

measures of income, consumption, and income poverty.

We expect most studies will focus on outcomes among children but would not exclude

studies that only report outcomes for adults.

(4)

We will also include studies even if they only report on the following types of behavioural

and attitudinal outcomes:

a.

water quantity used/consumed

b.

water treatment practices

c.

latrine use or defaecation practices (including construction of facilities for ‘triggering’

interventions)

d.

hygienic behaviour (e.g. observed hand washing practices, measurement of hand contamination,

microbial food contamination)

e.

willingness to pay.

We will exclude studies that only report measures of knowledge and attitudes; for

example, a hygiene education programme that reports the proportion that know that

bacteria can cause infections would be excluded.

Any adverse or unintended outcomes found to be reported, but not captured in the above

list, will be included.

Criteria for including and excluding studies

Types of study designs

This evidence gap map will include impact evaluations and systematic reviews of the

effectiveness of technologies and intervention mechanisms. Impact evaluations are

defined as programme evaluations or field experiments that use quantitative approaches

applied to experimental or observational data to measure the effect of a programme

relative to a counterfactual representing what would have happened to the same group

in absence of the programme. Impact evaluations may also test different programme

designs. We will include both completed and on‐going impact evaluations and systematic

reviews; to capture the latter, we will include prospective study records in trial

registries or protocols when available. We will include a broad range of intervention

study designs in order for the map to provide a comprehensive look at the evidence

provided by researchers working in the sector in different disciplines (e.g. epidemiology,

econometrics). We include randomised and non‐randomised controlled studies. We also

include methods such as natural experiments which may provide ‘as‐if randomised’ evidence

when well conducted (Waddington et al., 2017). We allow broader inclusion criteria

for particular outcomes, such as case‐control studies in the case of mortality, which

may not be ethically collected in trials, and uncontrolled before versus after for

time‐use outcomes, which are crucially important for water collectors and which arguably

do not require controls (White and Gunnarson, 2008).

Study design criteria for includable intervention studies are as follows:

a)

Prospective studies allocating the participants to the intervention using randomised

or quasi‐randomised mechanisms at individual or cluster levels.

a.

Randomised control trial (RCT) with assignment at individual or cluster level (e.g.

clustering at village, school, health facility)

b.

Quasi‐RCT using a quasi‐random method of prospective assignment (e.g. alternation

of clusters)

b)

Non‐randomised designs with selection on unobservables:

a.

Natural experiments using methods such as regression discontinuity (RD)

b.

Panel data or pseudo‐panels with analysis to account for time‐invariant unobservables

(e.g. difference‐in‐difference, DID, or fixed‐ or random‐effects models)

c.

Cross‐sectional studies using multi‐stage or multivariate approaches to account for

unobservables (e.g. instrumental variable, IV, or Heckman two‐step estimation approaches)

c)

Non‐randomised designs with selection on observables:

a.

Cross‐sectional or panel (controlled before and after) studies with an intervention

and comparison group using methods to match individuals and groups statistically (e.g.

PSM) or control for observable confounding in adjusted regression.

d)

The following impact evaluation study designs will only be included in the specific

circumstances described.

a.

Reflexive controls (pre‐test/post‐test with no control/comparison group) will be included

for studies reporting time use outcomes.

b.

Case‐control and cross‐sectional exposure designs will be included for studies conducted

at healthcare facilities measuring mortality.

e)

Studies explicitly described as systematic reviews and that describe methods used

for search, data collection, and synthesis.

We will include impact evaluations where the comparison/control group receive no intervention

(standard WASH access), a different WASH intervention, a placebo (e.g. school books)

or the study employs a pipeline (wait‐list) approach.

Treatment of qualitative research

We do not plan to include qualitative research.

Types of settings

All included impact evaluations must have been conducted in low‐ and middle‐income

countries (LMICs) as defined by the World Bank at the time of the intervention. We

will also exclude systematic reviews only containing evidence from high‐income countries.

We will include studies in challenging circumstances such as refugee camps, but exclude

studies which are conducted under outbreak conditions, such as epidemics of cholera

(‘extremely watery diarrhoea’) as this map aims to describe the evidence on what works

under normal conditions.

As we are focusing on personal and household WASH interventions, we will exclude studies

that look at WASH interventions in agriculture, commercial food preparation, and ones

that focus on animal excreta. We will, however, include WASH interventions at medical

facilities if they meet the above intervention definitions. Studies on medicalised

hygiene (such as sterilising wounds) will be excluded.

Status of studies

We will search for and include completed and on‐going studies. We will not exclude

any studies based on language or publication status or publication date.

Search strategy and status of studies

We will automatically include all studies that were included in the 2014 evidence

gap map for which thorough searches were conducted for both published and ‘grey’ literature.

Therefore, the search strategy will cover two main components: updating the searches

already conducted from February 2014 onwards, and conducting new electronic searches

for the expanded scope from 2000 onwards. We will use the following strategies to

identify completed and on‐going new potential studies:

1)

Database and trial registry searches: We will search MEDLINE(R) (Ovid), Embase (Ovid),

CAB Global Health (Ovid), CAB Abstracts (Ovid), Cochrane Library, ERIC (Proquest),

Social Sciences Citation Index (Web of Science), Social Sciences Premium Collection

(Proquest), Popline, WHO Global Health Library, Econlit (Ovid), Ebsco Discovery, and

Campbell Library.

2)

Organisation searches: We will search for literature using 3ie's impact evaluation

database and through the online repositories of organisations who are known to produce

impact evaluations and systematic reviews of WASH interventions. These include the

Asian Development Bank, African Development Bank, Inter‐American Development Bank,

Department for International Development, IMPROVE International, International Water

and Sanitation Centre (IRC), Oxfam, UNICEF, US Agency for International Development,

WaterAid, the World Bank (DIME, Impact Evaluations, IEG) (Table 5).

3)

Bibliographic searches: Several recent systematic reviews (e.g. De Buck et al., 2017;

Benova, et al., 2014) are relevant to topics in our expanded scope and we will screen

these systematic reviews to locate additional primary studies.

4)

We will also conduct bibliographic back‐referencing of reference lists of all included

systematic reviews to identify additional primary studies and systematic reviews.

Table 5

Organisation hand‐searches

Organizations

Website

3ie

3ie water and sanitation sector

Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J‐PAL)

J‐PAL evaluations

African Development Bank

African Development Bank evaluation reports

Asian development Bank

ADB Impact evaluation studies

CEGA (University of California Center for Effective Global Action)

CEGA water and sanitation research projects

Department for International Development Research for Development

Research for Development outputs in water and sanitation

IMPROVE International

WASH organisations with independent evaluations

International Water and Sanitation Centre (IRC)

http://www.washdoc.info/docsearch/results?lmt=20&txt=water+sanitation+impact+evaluation&combine=all&field=&language=&mediatype=&dateset=since&date=0

Innovations for Poverty Action (IPA)

IPA WASH projects

Inter‐American Development Bank

Office of Evaluation and Oversight: project and impact evaluations in water & sanitation

Oxfam

Water sanitation and hygiene evaluation and research reports

USAID

USAID development experience clearinghouse

UNICEF

UNICEF evaldatabase

World Bank Development Impact Evaluation (DIME)

DIME)

World Bank Independent Evaluation Group (IEG)

IEG Systematic reviews and impact evaluations

Appendix B presents an example of the search strings used for publication databases

and search engines; it includes terms for the suitable interventions, regions, and

methodologies.

Screening and selection of studies

We will use EPPI reviewer to assess studies for inclusion at both the title / abstract

and full‐text screening stages. Due to time and resource constraints, at the title

/ abstract stage, we will use EPPI reviewer's machine learning capabilities to prioritise

studies in order of likelihood of inclusion. We will screen until we are no longer

finding any studies to include (at least 50 studies with 0 includes). Two researchers

will screen each title / abstract and each full‐text. Any disagreements on inclusion

will be resolved through discussion.

Data extraction, coding and management

For impact evaluations, we will use a standardised data extraction form to extract

descriptive data from all studies meeting our inclusion criteria. Data extracted from

each study will include bibliographic details, intervention types and descriptions,

outcome types and descriptions, study design, context / geographical information,

details on the comparison group, and on the quality of the implementation. We will

also extract data on the sex disaggregation of outcomes.

A full list of data to be extracted is described in the coding tool in Appendix C;

this tool will be piloted to ensure consistency in coding and resolve any issues or

ambiguities. A single researcher will conduct the data extraction for each study;

however, all coders will be trained on the tool before starting and a sample will

be double coded to check for consistency.

For systematic reviews, a modified version of the tool will be developed for the data

extraction. All systematic reviews for inclusion will undergo a critical appraisal

following the 3ie systematic review database protocol for appraisal of systematic

reviews (3ie, n.d.). Critical appraisals will be completed by one experienced researcher.

Quality Appraisal

We will critically appraise included systematic reviews according to the 3ie tool

(3ie, n.d.) which draws on Lewin et al. (2009). The tool appraises systematic review

conduct, analysis and reporting, guiding appraisers towards an overall judgement of

low, medium and high confidence in the review findings. We will assess primary studies

on design only (randomised versus non‐randomised assignment and method of analysis).

We will not be critically appraising the quality of the included impact evaluations,

but will collect data on study design. For the purpose of the present map it is not

necessary to critically appraise the impact evaluations, beyond indicating whether

the evidence is from randomised, natural experiment, or non‐randomised studies, as

the systematic reviews provide overviews of the body of evidence, including their

quality, where they exist. A major purpose the map is to provide access to the body

of work on particular outcomes and interventions to encourage further syntheses of

those studies by WASH sector researchers.

Analysis and Presentation

Unit of Analyses

Where multiple papers exist on the same study (e.g. a working paper and a published

version), the most recent open access version will be included in the evidence map.

If the versions report on different outcomes, an older version will be included for

the outcomes not covered in later versions.

Planned analyses

The matrix and filters are described above and in Appendix A. In brief, the matrix

will display interventions mechanisms (direct provision, health messaging, psycho‐social

triggering and systems‐based approaches) against outcomes along the causal chain (behaviour

change and attitudes, health outcomes, nutrition outcomes, socio‐economic outcomes).

It will be searchable by several filters including WASH technology (water quantity,

water quality, sanitation, hygiene, multiple interventions), location (households,

communities, schools and health facilities), study design (randomised and non‐randomised

assignment), country and global region, and location (rural, urban, slum, refugee

camp). The report will include descriptions of the evidence base according to these

categories and present a global map, tables and figures presenting descriptive information

about these characteristics. The report will present separately evidence from primary

research (impact evaluations) and synthesis (systematic reviews).

Presentation

The matrix and filters are described above and in Appendix A. In brief, the matrix

will display interventions mechanisms (direct provision, health messaging, psycho‐social

triggering and systems‐based approaches) against outcomes along the causal chain (behaviour

change and attitudes, health outcomes, nutrition outcomes, socio‐economic outcomes).

It will be searchable by several filters including WASH technology (water quantity,

water quality, sanitation, hygiene, multiple interventions), location (households,

communities, schools and health facilities), study design (randomised and non‐randomised

assignment), country and global region, and location (rural, urban, slum, refugee

camp).

Stakeholder engagement

We have engaged stakeholders on the evidence matrix at various organisations who provide

WaSH sector policy and programmes. These include Aga Khan Foundation, the Independent

Evaluation Group of the World Bank, Japan International Cooperation Agency, Sanitation

and Hygiene Applied Research for Equity (SHARE) consortium, the Water Supply and Sanitation

Collaborative Council, and WaterAid.

EGM authors

Lead EGM author: The lead author is the person who develops and co‐ordinates the EGM

team, discusses and assigns roles for individual members of the team, liaises with

the editorial base and takes responsibility for the on‐going updates of the EGM.

Name:

Hugh Waddington

Title:

Senior Evaluation Specialist

Affiliation:

International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie)

Address:

London International Development Centre 36 Gordon Square

City, State, Province or County:

London

Post code:

WC1H 0PD

Country:

UK

Phone:

+44 207 958 8350

Email:

hwaddington@3ieimpact.org

Co‐authors:

Name:

Hannah Chirgwin

Title:

Research Associate

Affiliation:

3ie

Address:

London International Development Centre 36 Gordon Square

City, State, Province or County:

London

Post code:

WC1H 0PD

Country:

UK

Phone:

+44 207 958 8352

Email:

hchirgwin@3ieimpact.org

Name:

John Eyers

Title:

Information Retrieval Specialist

Affiliation:

3ie

Name:

Yashaswini PrasannaKumar

Title:

Public Policy Research Consultant

Affiliation:

3ie

Name:

Duae Zehra

Title:

Research Assistant

Affiliation:

University College London

Name:

Sandy Cairncross

Title:

Professor

Affiliation:

London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

Roles and responsibilities

Content: Sandy Cairncross has substantial expertise in water, sanitation and hygiene

interventions for the control of disease. Hugh Waddington led a previous review of

WASH impacts.

Systematic review methods: Sandy Cairncross has led several major systematic reviews

of WASH interventions. Hugh Waddington led a previous systematic review and has supported

a large number of systematic reviews and meta‐analyses for 3ie and Campbell.

Information retrieval: John Eyers has substantial expertise in devising and running

systematic searches for published and unpublished literature, including for reviews

of WASH interventions.

Sources of support

We thank JICA and the Water Supply and Sanitation Collaborative Council (WSSCC) for

financial support. Ritsuko Yamagata, Jeff Tanner, Midori Makino, Ryotaro Hayashi and

Marie Gaarder provided helpful comments.

Declarations of interest

Sandy Cairncross has been involved in the development of sanitation and hygiene interventions

and he and Hugh Waddington have authored primary studies and systematic reviews that

may be eligible for inclusion in the evidence map. Inclusion decisions and critical

appraisal of any studies these two authors have been involved in will be undertaken

by other members of the team. We are not aware of any other conflicts that might affect

decisions taken in the review and results presented.

Preliminary timeframe

Approximate date for submission of the EGM: July 2018.

Plans for updating the EGM

This map is itself an update of a EGM published online in 2014. We plan to update

the map (or support others in doing so) when sufficient further studies and resources

become available.

Related collections

Most cited references47

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

Effect of hand hygiene on infectious disease risk in the community setting: a meta-analysis.

Allison Aiello, Rebecca Coulborn, Vanessa Perez … (2008)

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Water, sanitation and hygiene for the prevention of diarrhoea

Sandy Cairncross, Caroline Hunt, Sophie Boisson … (2010)

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

Handwashing and risk of respiratory infections: a quantitative systematic review

Tamer Rabie, Valerie A Curtis (2006)