- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

Supply and demand shocks in the COVID-19 pandemic: an industry and occupation perspective

Read this article at

Abstract

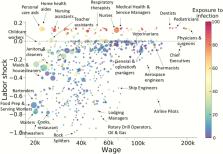

We provide quantitative predictions of first-order supply and demand shocks for the US economy associated with the COVID-19 pandemic at the level of individual occupations and industries. To analyse the supply shock, we classify industries as essential or non-essential and construct a Remote Labour Index, which measures the ability of different occupations to work from home. Demand shocks are based on a study of the likely effect of a severe influenza epidemic developed by the US Congressional Budget Office. Compared to the pre-COVID period, these shocks would threaten around 20 per cent of the US economy’s GDP, jeopardize 23 per cent of jobs, and reduce total wage income by 16 per cent. At the industry level, sectors such as transport are likely to be output-constrained by demand shocks, while sectors relating to manufacturing, mining, and services are more likely to be constrained by supply shocks. Entertainment, restaurants, and tourism face large supply and demand shocks. At the occupation level, we show that high-wage occupations are relatively immune from adverse supply- and demand-side shocks, while low-wage occupations are much more vulnerable. We should emphasize that our results are only first-order shocks—we expect them to be substantially amplified by feedback effects in the production network.

Related collections

Most cited references18

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

Estimates of the severity of coronavirus disease 2019: a model-based analysis

- Record: found

- Abstract: not found

- Report: not found

How Many Jobs Can be Done at Home?

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found