- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

County-Level COVID-19 Vaccination Coverage and Social Vulnerability — United States, December 14, 2020–March 1, 2021

research-article

Michelle M. Hughes , PhD

1

,

,

Alice Wang , PhD

1 ,

Marissa K. Grossman , PhD

1

,

2 ,

Eugene Pun , MPH

1

,

3 ,

Ari Whiteman , PhD

1

,

2 ,

Li Deng , PhD

1 ,

Elaine Hallisey , MA

2 ,

J. Danielle Sharpe , MS

1

,

2 ,

Emily N. Ussery , PhD

1 ,

Shannon Stokley , DrPH

1 ,

Trieste Musial , MS

2 ,

Daniel L. Weller , PhD

1 ,

Bhavini Patel Murthy , MD

1 ,

Laura Reynolds , MPH

1 ,

Lynn Gibbs-Scharf , MPH

1 ,

LaTreace Harris , MPH

1 ,

Matt D. Ritchey , DPT

1 ,

Robin L. Toblin , PhD

1

26 March 2021

Read this article at

There is no author summary for this article yet. Authors can add summaries to their articles on ScienceOpen to make them more accessible to a non-specialist audience.

Abstract

The U.S. COVID-19 vaccination program began in December 2020, and ensuring equitable

COVID-19 vaccine access remains a national priority.* COVID-19 has disproportionately

affected racial/ethnic minority groups and those who are economically and socially

disadvantaged (

1

,

2

). Thus, achieving not just vaccine equality (i.e., similar allocation of vaccine

supply proportional to its population across jurisdictions) but equity (i.e., preferential

access and administration to those who have been most affected by COVID-19 disease)

is an important goal. The CDC social vulnerability index (SVI) uses 15 indicators

grouped into four themes that comprise an overall SVI measure, resulting in 20 metrics,

each of which has national and state-specific county rankings. The 20 metric-specific

rankings were each divided into lowest to highest tertiles to categorize counties

as low, moderate, or high social vulnerability counties. These tertiles were combined

with vaccine administration data for 49,264,338 U.S. residents in 49 states and the

District of Columbia (DC) who received at least one COVID-19 vaccine dose during December

14, 2020–March 1, 2021. Nationally, for the overall SVI measure, vaccination coverage

was higher (15.8%) in low social vulnerability counties than in high social vulnerability

counties (13.9%), with the largest coverage disparity in the socioeconomic status

theme (2.5 percentage points higher coverage in low than in high vulnerability counties).

Wide state variations in equity across SVI metrics were found. Whereas in the majority

of states, vaccination coverage was higher in low vulnerability counties, some states

had equitable coverage at the county level. CDC, state, and local jurisdictions should

continue to monitor vaccination coverage by SVI metrics to focus public health interventions

to achieve equitable coverage with COVID-19 vaccine.

COVID-19 vaccine administration data are reported to CDC by multiple entities via

immunization information systems (IIS), the Vaccine Administration Management System,

or direct data submission.

†

Vaccination coverage was defined as the number of residents who received at least

one dose of COVID-19 vaccine during December 14, 2020–March 1, 2021, and whose data

were reported to CDC by March 6, 2021.

§

Total county population denominators used to create vaccination coverage estimates

were obtained from the U.S. Census Bureau 2019 Population Estimates Program.

¶

Social vulnerability data were obtained from the CDC SVI 2018 database,** which includes

metrics to identify communities that might need additional support during emergencies,

including the COVID-19 pandemic (Supplementary Figure 1, https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/104111).

County-level social vulnerability rankings for 15 SVI indicators, four SVI themes,

and the overall SVI (20 total SVI metrics) were used.

††

Each of the SVI metrics was categorized into national

§§

and state-specific

¶¶

tertiles*** (low, moderate, and high social vulnerability) based on their national

(among all U.S. counties) or state (among each state’s counties) rank.

Vaccination coverage (percentage of residents who received at least one COVID-19 vaccine

dose) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) within SVI tertiles were calculated for each

of the 20 SVI metrics for the national analyses, with jurisdictional exclusions based

on missing data for state of residence, missing data for county of residence (Hawaii,

which did not systematically report these data), or no available SVI metrics (eight

territories and freely associated states).

†††

A vaccination rate ratio (RR) and 95% CI for each SVI metric was calculated using

Wald’s unconditional maximum likelihood estimation to assess the relative differences

in vaccination coverage, comparing low and moderate vulnerability counties with high

vulnerability counties. The rate difference was also calculated to assess the difference

between SVI tertiles. Because of the large sample sizes, rather than using statistical

significance to determine meaningful differences between tertiles, a difference of

≥0.5 percentage points was used. State-level analyses for the overall SVI and four

SVI themes were conducted among states with more than three counties. In addition,

vaccination coverage for SVI metrics (national analyses) and SVI metrics within states

(state-level analyses) were normalized so that the sum across tertiles was one.

§§§

(When vaccination coverage is equally distributed among tertiles within an SVI metric,

the proportion of persons vaccinated in each SVI tertile is 0.33.) This activity was

reviewed by CDC and was conducted consistent with applicable federal law and CDC policy.

¶¶¶

During December 14, 2020–March 1, 2021, a total of 51,873,700 residents of 49 U.S.

states and DC received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine. County of residence

was available for 95.0% (49,264,338) of these records for analysis. National first-dose

vaccination coverage was 15.1%. For overall SVI, vaccination coverage was 1.9 percentage

points higher in low vulnerability counties than in high vulnerability counties (15.8%

versus 13.9%, respectively) (Table). The same pattern was found for the SVI themes

of socioeconomic status, household composition and disability status, and racial/ethnic

minority status and language, with the largest vaccination coverage disparity in the

socioeconomic status theme (difference of 2.5 percentage points). Vaccination coverage

was ≥0.5 percentage points lower in low vulnerability counties than in high vulnerability

counties for the following indicators: 1) population aged ≥65 years (2.3 percentage

points lower), 2) multiunit housing (1.3 percentage points lower), and 3) households

with no vehicle (0.7 percentage points lower) (Figure 1). Indicators associated with

similar coverage in low and high vulnerability counties were 1) percentage of persons

with a disability and 2) percentage of persons who speak English “less than well.”

Vaccination coverage was higher in low vulnerability counties than in high vulnerability

counties for the remaining 10 indicators. Among socioeconomic status indicators, the

largest disparity was the percentage of adults without a high school diploma (difference

of 2.8 percentage points between high and low vulnerability counties). The majority

of vaccination coverage differences between tertiles were <2 percentage points.

TABLE

Association between county-level COVID-19 vaccination coverage and social vulnerability

index (SVI) metrics among persons who received at least one vaccine dose (N = 49,264,338)

— United States, December 14, 2020–March 1, 2021*

SVI metric†

Vaccination coverage estimate§ (95% CI)

Rate ratio for relative differences in vaccination coverage (95% CI)**

Rate differences in vaccination coverage††

Low social vulnerability¶

Moderate social vulnerability¶

High social vulnerability¶

Low versus high estimate

Moderate versus high estimate

Low–high

Moderate–high

Overall SVI

15.8 (15.83−15.84)

15.6 (15.57−15.59)

13.9 (13.89−13.90)

1.1 (1.14−1.14)

1.1 (1.12−1.12)

1.94

1.69

Socioeconomic status

Total

15.9 (15.91−15.92)

15.0 (14.97−14.98)

13.5 (13.45−13.46)

1.2 (1.18−1.18)

1.1 (1.11−1.11)

2.46

1.52

Poverty

15.9 (15.85−15.86)

14.8 (14.79−14.80)

14.2 (14.21−14.23)

1.1 (1.11−1.12)

1.0 (1.04−1.04)

1.64

0.58

Unemployment

15.4 (15.38−15.40)

15.3 (15.30−15.31)

14.5 (14.54−14.55)

1.1 (1.06−1.06)

1.1 (1.05−1.05)

0.85

0.76

Per capita income

15.6 (15.57−15.58)

14.4 (14.35−14.37)

13.5 (13.45−13.48)

1.2 (1.16−1.16)

1.1 (1.07−1.07)

2.11

0.90

No high school diploma

16.0 (16.01−16.02)

15.3 (15.26−15.27)

13.2 (13.22−13.23)

1.2 (1.21−1.21)

1.2 (1.15−1.16)

2.79

2.04

Household composition and disability status

Total

15.6 (15.62−15.63)

14.4 (14.41−14.42)

14.2 (14.20−14.22)

1.1 (1.10−1.10)

1.0 (1.01−1.02)

1.42

0.21

Age ≥65 yrs

14.6 (14.58−14.59)

15.9 (15.89−15.91)

16.9 (16.90−16.92)

0.9 (0.86−0.86)

0.9 (0.94−0.94)

−2.32

−1.01

Age ≤17 yrs

16.6 (16.57−16.58)

15.5 (15.51−15.53)

13.6 (13.56−13.57)

1.2 (1.22−1.22)

1.1 (1.14−1.14)

3.01

1.95

Disability

15.1 (15.13−15.14)

15.0 (14.95−14.97)

14.9 (14.88−14.90)

1.0 (1.02−1.02)

1.0 (1.00−1.01)

0.24

0.07

Single parent

16.7 (16.68−16.70)

15.6 (15.55−15.56)

14.0 (13.99−14.00)

1.2 (1.19−1.19)

1.1 (1.11−1.11)

2.70

1.56

Racial/Ethnic minority status and language

Total

15.5 (15.45−15.48)

15.6 (15.56−15.58)

14.9 (14.90−14.91)

1.0 (1.04−1.04)

1.0 (1.04−1.05)

0.57

0.67

Racial/Ethnic minority

15.5 (15.51−15.54)

15.7 (15.66−15.67)

14.8 (14.75−14.76)

1.1 (1.05−1.05)

1.1 (1.06−1.06)

0.77

0.91

Limited English

15.3 (15.30−15.33)

15.5 (15.47−15.49)

14.9 (14.93−14.93)

1.0 (1.02−1.03)

1.0 (1.04−1.04)

0.38

0.55

Housing type and transportation

Total

14.8 (14.81−14.82)

15.3 (15.25−15.26)

15.0 (15.03−15.05)

1.0 (0.98−0.99)

1.0 (1.01−1.01)

−0.23

0.21

Multiunit housing

14.0 (13.96−13.99)

14.5 (14.49−14.51)

15.2 (15.24−15.24)

0.9 (0.92−0.92)

1.0 (0.95−0.95)

−1.26

−0.74

Mobile homes

15.2 (15.22−15.23)

15.1 (15.05−15.07)

14.0 (13.98−14.00)

1.1 (1.09−1.09)

1.1 (1.08−1.08)

1.24

1.07

Crowding

16.1 (16.08−16.10)

15.1 (15.09−15.11)

14.7 (14.65−14.66)

1.1 (1.10−1.10)

1.0 (1.03−1.03)

1.43

0.45

No vehicle

14.5 (14.49−14.51)

15.4 (15.35−15.36)

15.2 (15.15−15.16)

1.0 (0.96−0.96)

1.0 (1.01−1.01)

−0.66

0.20

Group quarters

15.9 (15.85−15.86)

14.8 (14.79−14.80)

14.2 (14.21−14.23)

1.1 (1.11−1.12)

1.0 (1.04−1.04)

1.64

0.58

Abbreviation: CI = confidence interval.

* Vaccines administered to residents of 49 U.S. states (excluding Hawaii) and the

District of Columbia during December 14, 2020–March 1, 2021, and reported to CDC by

March 6, 2021.

† SVI ranks counties according to 15 social factors (indicators): 1) percentage of

persons with incomes below poverty threshold, 2) percentage of civilian population

(aged ≥16 years) that is unemployed, 3) per capita income, 4) percentage of persons

aged ≥25 years with no high school diploma, 5) percentage of persons aged ≥65 years,

6) percentage of persons aged ≤17 years, 7) percentage of civilian noninstitutionalized

population with a disability, 8) percentage of single-parent households with children

aged <18 years, 9) percentage of persons who are racial/ethnic minorities (all persons

except non-Hispanic White), 10) percentage of persons aged ≥5 years who speak English

“less than well,” 11) percentage of housing in structures with ≥10 units (multiunit

housing), 12) percentage of housing structures that are mobile homes, 13) percentage

households with more persons than rooms (crowding), 14) percentage of households with

no vehicle available, and 15) percentage of persons in group quarters. Estimates are

created using 2014–2018 (5-year) data from the American Community Survey. The 15 indicators

are categorized into four themes: 1) socioeconomic status (indicators 1–4), 2) household

composition and disability (indicators 5–8), 3) racial/ethnic minority status and

language (indicators 9 and 10), and 4) housing type and transportation (indicators

11–15). Overall SVI includes all 15 indicators as a composite measure. Additional

details are available (https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/placeandhealth/svi/documentation/SVI_documentation_2018.html).

§ Total county population denominators used to create vaccination coverage estimates

were obtained from the U.S. Census Bureau 2019 Population Estimates Program (https://www.census.gov/data/datasets/time-series/demo/popest/2010s-counties-total.html).

Vaccination coverage was calculated as the total number of vaccine doses administered

divided by the total population size for included counties in each SVI tertile.

¶ Counties were assigned to tertiles (low, moderate, and high social vulnerability)

for each of the 20 SVI ranking metrics.

** Rate ratios compare the relative difference in vaccination coverage between SVI tertiles;

high social vulnerability is the reference category.

†† Rate differences compare the difference in vaccination coverage between SVI tertiles;

high social vulnerability is the reference category. Vaccination coverage differences

of ≥0.5 percentage points were considered meaningful differences between SVI tertiles.

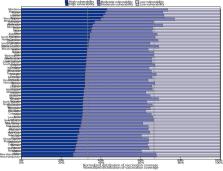

FIGURE 1

Distribution of county-level* COVID-19 vaccination coverage among persons who received

at least one vaccine dose (N = 49,264,338),

†

by social vulnerability index (SVI) metric

§

and tertile — United States, December 14, 2020–March 1, 2021

* Counties were assigned to tertiles (low, moderate, and high) for overall SVI. Data

are presented as a 100% stacked bar chart (normalized across states), with the length

of each bar segment representing the proportion of total vaccination coverage for

each SVI tertile. When proportions of vaccination coverage are equal among SVI tertiles,

each proportion represents 0.33, represented by the vertical lines. When proportions

of vaccination coverage estimates are not equally distributed among SVI tertiles,

then proportions do not align with threshold lines representing 0.33.

† Vaccines administered to residents of 49 U.S. states (excluding Hawaii) and the

District of Columbia during December 14, 2020–March 1, 2021, and reported to CDC by

March 6, 2021.

§ SVI ranks counties according to 15 social factors (indicators): 1) percentage of

persons with incomes below poverty threshold, 2) percentage of civilian population

(aged ≥16 years) that is unemployed, 3) per capita income, 4) percentage of persons

aged ≥25 years with no high school diploma, 5) percentage of persons aged ≥65 years,

6) percentage of persons aged ≤17 years, 7) percentage of civilian noninstitutionalized

population with a disability, 8) percentage of single-parent households with children

aged <18 years, 9) percentage of persons who are racial/ethnic minorities (i.e., all

persons except those who are non-Hispanic White), 10) percentage of persons aged ≥5

years who speak English “less than well,” 11) percentage of housing in structures

with ≥10 units (multiunit housing), 12) percentage of housing structures that are

mobile homes, 13) percentage households with more persons than rooms (crowding), 14)

percentage of households with no vehicle available, and 15) percentage of persons

in group quarters. Estimates are created using 2014–2018 (5-year) data from the American

Community Survey. The 15 indicators are categorized into four themes: 1) socioeconomic

status (indicators 1–4), 2) household composition and disability (indicators 5–8),

3) racial/ethnic minority status and language (indicators 9 and 10), and 4) housing

type and transportation (indicators 11–15). Overall SVI includes all 15 indicators

as a composite measure.

This figure is a bar chart showing the distribution of COVID-19 vaccination coverage

among persons who received at least one dose during December 14, 2020–March 1, 2021,

for U.S. counties with low, moderate, and high social vulnerability according to 15

social vulnerability index indicators.

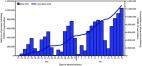

In the state-level analyses, across overall SVI and all four themes, higher vaccination

coverage in high vulnerability counties compared with low vulnerability counties (i.e.,

equity) was found in two states (Arizona and Montana) (Figure 2) (Supplementary Table,

Supplementary Figure 2, https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/104111). Three other states

had higher vaccination coverage in high vulnerability counties than in low vulnerability

counties for the overall SVI and three of four themes (Alaska, all except the socioeconomic

status theme, and Minnesota and West Virginia, all except the racial/ethnic minority

status and language theme). Vaccination disparities were observed in 31 states (overall

SVI measure); in 11 of these states, the disparity was found in all four SVI themes.

FIGURE 2

Distribution of county-level* COVID-19 vaccination coverage among persons who received

at least one vaccine dose (N = 49,019,117),

†

by state and overall social vulnerability index (SVI) tertile — United States, December

14, 2020–March 1, 2021

* Counties were assigned to tertiles (low, moderate, and high) for overall SVI. Data

are presented as a 100% stacked bar chart (normalized across states), with the length

of each bar segment representing the proportion of total vaccination coverage for

each SVI tertile. When proportions of vaccination coverage are equal among SVI tertiles,

each proportion represents 0.33, represented by the vertical lines. When proportions

of vaccination coverage estimates are not equally distributed among SVI tertiles,

then proportions do not align with threshold lines representing 0.33.

† Vaccines administered to residents of 48 U.S. states (excluding Delaware, the District

of Columbia, and Hawaii) during December 14, 2020–March 1, 2021, and reported to CDC

by March 6, 2021.

This figure is a bar chart showing the distribution of COVID-19 vaccination coverage

among persons who received at least one dose, by state, during December 14, 2020–March

1, 2021, for U.S. counties with low, moderate, and high social vulnerability according

to the social vulnerability index.

Discussion

Ensuring equitable COVID-19 vaccine access is a priority for the U.S. COVID-19 vaccination

program.**** In the first 2.5 months of the program, vaccination coverage was lower

in high vulnerability counties nationwide, demonstrating that additional efforts are

needed to achieve equity in vaccination coverage for those who have been most affected

by COVID-19 (

3

). Improving COVID-19 vaccination coverage in communities with high proportions of

racial/ethnic minority groups and persons who are economically and socially marginalized

is critical because these populations have been disproportionately affected by COVID-19–related

morbidity and mortality (

4

–

6

). Monitoring community-level metrics is essential to informing tailored, local vaccine

delivery efforts, which might reduce inequities. Public health officials can investigate

whether disparities are occurring because of access problems (e.g., vaccine supply, vaccination

clinic availability, and lack of prioritization of vulnerable groups) or other challenges,

such as vaccine hesitancy. Vaccination promotion, outreach, and administration might

focus on high vulnerability populations within counties (e.g., providing resources

to federally qualified health centers when socioeconomic disparities are identified).

††††

Vaccination coverage was consistently lower in high vulnerability counties than in

low vulnerability counties for the socioeconomic status indicators (i.e., poverty,

unemployment, low income, and no high school diploma); the coverage disparity was

largest for the education indicator. However, equal vaccination coverage in counties

with low and high social vulnerability was observed for the indicators relating to

the percentages of persons who speak English less than well and with persons with

a disability, which is encouraging in light of the disproportionate incidence of COVID-19

in these populations.

§§§§

Higher coverage in counties with large proportions of older adults was consistent

with the prioritization of this age group early in the vaccination program; however,

the higher coverage in counties with lower percentages of households with a vehicle

available was unexpected and warrants further investigation. Despite these positive

findings, equity in access to COVID-19 vaccination has not been achieved nationwide.

COVID-19 vaccination equity varied among states. In most states, coverage was higher

in low vulnerability counties than in high vulnerability counties. Despite this, states

such as Arizona and Montana achieved higher vaccination coverage in high vulnerability

counties across SVI metrics. Practices in states with high equity included 1) prioritizing

persons in racial/ethnic minority groups during the early stages of the vaccine program

implementation, 2) actively monitoring and addressing barriers to vaccination in vulnerable

communities, 3) directing vaccines to vulnerable communities, 4) offering free transportation

to vaccination sites, and 5) collaborating with community partners, tribal health

organizations, and the Indian Health Service.

¶¶¶¶

More investigation is needed to understand these differences to identify best practices

to achieve COVID-19 vaccination equity.

These findings demonstrate that estimates for overall SVI obscured variations among

SVI themes and that SVI themes masked variations among indicators within a theme group.

In addition, the national coverage estimates by SVI metrics did not capture the wide

variation among states. These results highlight the importance of examining individual

SVI indicators in addition to the composite SVI measure and themes to monitor equitable

vaccine administration. State and local jurisdictions should also consider analyzing

SVI metrics at the level of the census tract (when these data are available).

The findings in this report are subject to at least five limitations. First, because

specific populations were prioritized for vaccination in each state, the differences

observed might be due, in part, to prioritization based on age, occupational exposures,

and underlying health conditions. Second, these associations are ecological and reported

for population-based metrics rather than individual-level vulnerability data. With

only age, sex, and limited race/ethnicity data available at the national level, use

of these population-based metrics is an important method to evaluate socioeconomic

and demographic disparities. Third, although the geographic unit of analysis was the

county, the vulnerabilities and vaccination coverage rates might vary within counties;

state and local jurisdictions might prioritize vaccination efforts for high vulnerability

communities in smaller geographic units (e.g., census tracts). Fourth, SVI metrics

do not include all population characteristics that could be used to identify disparities

and focus vaccination efforts, such as lack of Internet access (

7

). Finally, coverage was calculated based on total population, and vaccines authorized

for use during the study period were only recommended for persons aged ≥16 or ≥18

years.*****

The results of this study indicate that COVID-19 vaccination coverage was lower in

high vulnerability counties than in low vulnerability counties, a finding largely

driven by socioeconomic disparities. As vaccine supply increases and administration

expands to additional priority groups, CDC, state, and local jurisdictions should

continue to monitor vaccination levels by SVI metrics to aid in the development of

community efforts to improve vaccination access, outreach, and administration among

populations most affected by COVID-19.

Summary

What is already known about this topic?

COVID-19 has disproportionally affected racial/ethnic minority groups and persons

who are economically and socially disadvantaged. Ensuring equitable COVID-19 vaccine

coverage is a national priority.

What is added by this report?

In the first 2.5 months of the U.S. vaccination program, high social vulnerability

counties had lower COVID-19 vaccination coverage than did low social vulnerability

counties. Although vaccination coverage estimates by county-level social vulnerability

varied widely among states, disparities in vaccination coverage were observed in the

majority of states.

What are the implications for public health practice?

Continued monitoring of vaccination coverage by social vulnerability metrics is critical for

developing tailored, local vaccine administration and outreach efforts to reduce COVID-19

vaccination inequities.

Related collections

Most cited references5

- Record: found

- Abstract: not found

- Article: not found

Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities Related to COVID-19

Leo Lopez, Louis H. Hart, Mitchell Katz (2021)

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

Social Vulnerability and Racial Inequality in COVID-19 Deaths in Chicago

Sage Kim, Wendy Bostwick (2020)

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Demographic Characteristics of Persons Vaccinated During the First Month of the COVID-19 Vaccination Program — United States, December 14, 2020–January 14, 2021

Elizabeth M. Painter, Emily Ussery, Anita Patel … (2021)