- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Effects of covid-19 pandemic on life expectancy and premature mortality in 2020: time series analysis in 37 countries

Read this article at

Abstract

Objective

To estimate the changes in life expectancy and years of life lost in 2020 associated with the covid-19 pandemic.

Setting

37 upper-middle and high income countries or regions with reliable and complete mortality data.

Participants

Annual all cause mortality data from the Human Mortality Database for 2005-20, harmonised and disaggregated by age and sex.

Main outcome measures

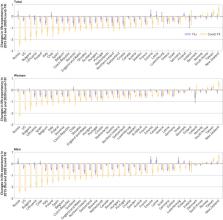

Reduction in life expectancy was estimated as the difference between observed and expected life expectancy in 2020 using the Lee-Carter model. Excess years of life lost were estimated as the difference between the observed and expected years of life lost in 2020 using the World Health Organization standard life table.

Results

Reduction in life expectancy in men and women was observed in all the countries studied except New Zealand, Taiwan, and Norway, where there was a gain in life expectancy in 2020. No evidence was found of a change in life expectancy in Denmark, Iceland, and South Korea. The highest reduction in life expectancy was observed in Russia (men: −2.33, 95% confidence interval −2.50 to −2.17; women: −2.14, −2.25 to −2.03), the United States (men: −2.27, −2.39 to −2.15; women: −1.61, −1.70 to −1.51), Bulgaria (men: −1.96, −2.11 to −1.81; women: −1.37, −1.74 to −1.01), Lithuania (men: −1.83, −2.07 to −1.59; women: −1.21, −1.36 to −1.05), Chile (men: −1.64, −1.97 to −1.32; women: −0.88, −1.28 to −0.50), and Spain (men: −1.35, −1.53 to −1.18; women: −1.13, −1.37 to −0.90). Years of life lost in 2020 were higher than expected in all countries except Taiwan, New Zealand, Norway, Iceland, Denmark, and South Korea. In the remaining 31 countries, more than 222 million years of life were lost in 2020, which is 28.1 million (95% confidence interval 26.8m to 29.5m) years of life lost more than expected (17.3 million (16.8m to 17.8m) in men and 10.8 million (10.4m to 11.3m) in women). The highest excess years of life lost per 100 000 population were observed in Bulgaria (men: 7260, 95% confidence interval 6820 to 7710; women: 3730, 2740 to 4730), Russia (men: 7020, 6550 to 7480; women: 4760, 4530 to 4990), Lithuania (men: 5430, 4750 to 6070; women: 2640, 2310 to 2980), the US (men: 4350, 4170 to 4530; women: 2430, 2320 to 2550), Poland (men: 3830, 3540 to 4120; women: 1830, 1630 to 2040), and Hungary (men: 2770, 2490 to 3040; women: 1920, 1590 to 2240). The excess years of life lost were relatively low in people younger than 65 years, except in Russia, Bulgaria, Lithuania, and the US where the excess years of life lost was >2000 per 100 000.

Related collections

Most cited references59

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Physical distancing, face masks, and eye protection to prevent person-to-person transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found