- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Persistence and decay of human antibody responses to the receptor binding domain of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein in COVID-19 patients

Read this article at

Abstract

IgM and IgA responses to SARS-CoV-2 RBD in severe COVID patients decay rapidly, while IgG responses persist for over 3 months.

Abstract

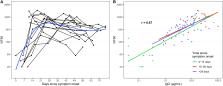

We measured plasma and/or serum antibody responses to the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the spike (S) protein of SARS-CoV-2 in 343 North American patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 (of which 93% required hospitalization) up to 122 days after symptom onset and compared them to responses in 1548 individuals whose blood samples were obtained prior to the pandemic. After setting seropositivity thresholds for perfect specificity (100%), we estimated sensitivities of 95% for IgG, 90% for IgA, and 81% for IgM for detecting infected individuals between 15 and 28 days after symptom onset. While the median time to seroconversion was nearly 12 days across all three isotypes tested, IgA and IgM antibodies against RBD were short-lived with median times to seroreversion of 71 and 49 days after symptom onset. In contrast, anti-RBD IgG responses decayed slowly through 90 days with only 3 seropositive individuals seroreverting within this time period. IgG antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 RBD were strongly correlated with anti-S neutralizing antibody titers, which demonstrated little to no decrease over 75 days since symptom onset. We observed no cross-reactivity of the SARS-CoV-2 RBD-targeted antibodies with other widely circulating coronaviruses (HKU1, 229 E, OC43, NL63). These data suggest that RBD-targeted antibodies are excellent markers of previous and recent infection, that differential isotype measurements can help distinguish between recent and older infections, and that IgG responses persist over the first few months after infection and are highly correlated with neutralizing antibodies.

Related collections

Most cited references19

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

Clinical and immunological assessment of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

Profiling Early Humoral Response to Diagnose Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19)

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found