- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Global resource shortages during COVID-19: Bad news for low-income countries

research-article

Devon E. McMahon

1

,

2 ,

Gregory A. Peters

1 ,

Louise C. Ivers

1

,

3 ,

Esther E. Freeman

1

,

2

,

4

,

*

6 July 2020

There is no author summary for this article yet. Authors can add summaries to their articles on ScienceOpen to make them more accessible to a non-specialist audience.

Abstract

The world’s wealthiest countries have been gripped by resource shortages, including

shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE) and ventilators, during the coronavirus

disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic [1, 2]. In order to guarantee these resources for

their own nation’s health workers, governments around the world are bargaining for

their share in a strangled global supply chain. For example, countries such as Taiwan,

Thailand, Russia, Germany, the Czech Republic, and Kenya have blocked the export of

all face masks [3]. There have additionally been reports of PPE and ventilator exports

being intercepted and delivered to the country with the highest bid, aptly referred

to as acts of “modern piracy” [3].

Undeniably, securing PPE for health workers and respiratory devices for patients is

a critical part of overcoming the COVID-19 pandemic. However, we must not forget that

for many hospitals, these resources have never been in abundant supply. Instead, PPE

and respiratory devices are scarce commodities for many hospitals in low-income countries

(gross national income per capita ≤US$1,025) under the best of circumstances, with

health crises such as the 2014–2016 West African Ebola epidemic highlighting gaps

in the global PPE supply [4]. Indeed, deaths from Ebola were concentrated among healthcare

providers, with 8.1% of the total health workforce in Liberia and 6.9% in Sierra Leone

dying from Ebola [5]. Hospitals in low-income countries rely on the same supply chains

as hospitals in wealthy countries to import medical supplies but have significantly

less bargaining power to secure resources [6]. Therefore, resource grabs by high-income

countries will likely have devastating effects on low-income countries as COVID-19

continues to spread globally [6, 7]. Already, UNICEF reports that the organization

has only been able to acquire one-tenth of the 240 million masks requested by low-income

countries [6].

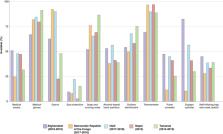

To better elucidate COVID preparedness in low-income countries, we combined data from

all service provision assessments (SPAs) conducted in nationally representative surveys

of hospitals within the past 5 years in low-income countries, which included Afghanistan,

Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Haiti, Nepal, and Tanzania [8]. Our analysis

of hospital general clinics confirms limited quantities of PPE, with only 24% to 51%

of hospitals reporting any type of face mask, 22% to 92% medical gowns, and 3% to

22% eye protection (Fig 1). Sanitation supplies were also scarce, with 52% to 87%

of hospitals recording soap plus running water and 38% to 56% alcohol-based hand sanitizer.

We found further gaps in ability to provide care for respiratory conditions, again

demonstrating under-investment in hospital-based services [9]. The hospitals analyzed

lacked pulse oximeters (12%–48% available), oxygen tanks (10%–82%), and bag-masks

necessary for basic resuscitation (28%–45%). As has been noted by prior studies, more

advanced respiratory support such as intensive care unit (ICU) care and ventilators

are even scarcer [10].

10.1371/journal.pntd.0008412.g001

Fig 1

Availability of hospital clinic PPE, sanitation, and functional diagnostics and therapeutics

across nationally representative samples of hospitals in 5 low-income countries.

PPE, personal protective equipment.

An important part of addressing the COVID-19 pandemic is adequate testing at the community

level. In addition to current shortages of COVID-19 testing globally [2, 11], the

ability to offer COVID-19 testing will likely be further constrained in low-income

countries due to already limited diagnostic capacity. For example, SPA data show that

fewer than 20% of hospitals, besides those in Tanzania, were able to measure CD4 count

for HIV monitoring. Additionally, there is limited ability to provide routine childhood

vaccination in hospitals in Afghanistan (35%), DRC (14%), Haiti (57%), and Nepal (60%),

underscoring the potential for gaps in the ability to transport, store, and deliver

vaccines if eventually available for COVID-19.

With COVID-19 causing unprecedented resource shortages in the world’s wealthiest countries,

already limited healthcare commodities will likely become even scarcer in low-income

countries. There have been some rapid adjustments in the global supply chain, with

China increasing its output of medical masks to 12 times previous levels [3]. But

with prices for PPE and respiratory devices soaring, which hospitals will be able

to afford them?

In the West African Ebola epidemic, investment in high-quality PPE and infection control

training were important components of halting the spread of disease [12], and where

this was lacking, nosocomial spread was clearly worse [13]. In response to the current

COVID-19 challenge, countries such as Afghanistan and Nepal have started manufacturing

their own supplies of PPE and basic life support equipment, but this is not likely

to be a feasible approach for all countries [14, 15].

Continued local as well as international action is needed to ensure access to PPE

for all health workers and respiratory support for all patients, not just for those

living in resource-abundant countries. As COVID-19 therapeutics and vaccines emerge,

additional international commitment will be necessary to ensure global access. Equity

requires no less.

Related collections

Most cited references7

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

Critical Supply Shortages — The Need for Ventilators and Personal Protective Equipment during the Covid-19 Pandemic

Megan Ranney, Valerie Griffeth, Ashish Jha (2020)

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Sourcing Personal Protective Equipment During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Edward Livingston, Angel Desai, Michael Berkwits (2020)

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

COVID-19 and risks to the supply and quality of tests, drugs, and vaccines

Paul N. Newton, Katherine Bond, Moji Adeyeye … (2020)