Introduction

South Africa's electricity sector has been inextricably bound up with the country's dependence on abundant coal resources and cheap labour for the generation of cheap electricity for minerals-based, export-oriented industry. Enmeshed within core political and economic interests that have given rise to a historically specific system of accumulation, this forms the essence of the country's ‘minerals–energy complex’ (henceforth MEC) (Fine and Rustomjee 1996). However, significant changes to the electricity sector in recent years, including rising tariffs and a supply-side crisis, have been followed by the launch of a procurement process for privately generated renewable electricity. This paper questions the extent to which the introduction of these utility-scale renewable energy projects into South Africa's coal-dominated electricity supply can be considered a ‘low-carbon transition’ in the country's MEC. The paper asks: how and why has this renewable energy ‘niche’ emerged in South Africa at this time? Who and what has been involved in bringing this niche about? And what is preventing this niche from bringing about a broader transition in South Africa's MEC? In light of recent policy developments in the electricity sector and with a focus on the wind industry, this paper examines how low-carbon initiatives in South Africa's electricity sector are being integrated into a high-carbon and electricity-intensive industrial infrastructure which has a high inequality of access, and limited benefits for labour and the energy-poor (Hallowes and Munnik 2007).1

The paper firstly sets out its analytical framework, which fuses political economy perspectives informed by the MEC with the multi-level perspective on socio-technical transitions (Geels and Schot 2007). The creation of this framework, which builds on earlier studies (Baker 2012, Baker, Newell and Philips 2014) allows us to tackle an issue that is at once political, economic, social, environmental and technological. It also facilitates an analysis of conflicts between state entities, the underlying interests of dominant actors and beneficiaries of the country's electricity sector, and shifting capital interests in electricity generation.

A description of the minerals–energy complex is then given as the key configuration of the socio-technical ‘regime’ in question, and in which the country's electricity sector and the coal that is used to generate it is embedded. In contrast to the coal-fired power plants run by the monopoly utility Eskom, which have generated the bulk of the country's electricity to date, South Africa's grid-connected renewable energy sector is being developed by independent power producers (IPPs). Following a supply-side crisis within the MEC, the paper explains the recent regulatory changes that have facilitated the emergence of a renewable electricity generation industry and examines how this renewable energy ‘niche’, backed by private sources of finance and investment, is benefitting from national subsidies under the country's renewable energy independent power producers’ procurement programme (RE IPPPP).

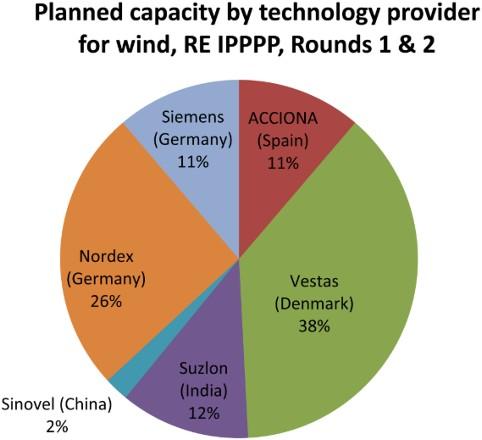

The paper then examines the wind industry as a subsector of the renewable energy niche, with a focus on stakeholders involved in projects approved in the first two rounds of the RE IPPPP. This is in order to demonstrate how new players are being integrated into South Africa's electricity generation sector, alongside a reconfiguration of some key MEC stakeholders, notably South Africa's second largest coal producer, Exxaro. The paper further considers how international trends in wind technology manufacturing and project development are playing out in South Africa. While the original leaders of the market such as Danish Vestas and German Siemens and Nordex still dominate, emerging market companies such as India's Suzlon and China's Sinovel are now beginning to compete. Finally, the paper considers possibilities and pitfalls for the sustainability of the wind industry given that, despite potentially positive requirements for local content and socio-economic development under the RE IPPPP, renewable energy may become a vested interest in its own right and in turn a new form of accumulation that may have limited impacts on the reduction of energy poverty and historical inequalities.

The political economy of socio-technical transitions

The term socio-technical transitions is used to mean deep structural changes in systems such as energy, transport and water to sustainable ends, involving complex reconfigurations of technology, infrastructure, policy, scientific knowledge and social behaviours over time. (Geels 2011, 24). Within a socio-technical system, technologies are embedded within complex socio-political and economic networks (Smith and Stirling 2007, 353), geophysical factors, institutions and infrastructures (Rip and Kemp 1998, 338). In this sense, any low-carbon, socio-technical transition or system innovation requires fundamental shifts in the structures of a technological regime or paradigm (Freeman and Perez 1988), implying considerable changes on the supply and demand sides and in technological development, policies, infrastructure and demand. The wide-ranging literature on socio-technical transitions draws from evolutionary economics (Dosi 1988), the sociology of technology (Hughes 1983) and, more recently, political science and theories of governance (Meadowcroft 2011).

There are various different strands within the socio-technical transitions literature (cf. Geels and Schot 2007) from both an analytical perspective as well as a prescriptive approach to technological change in the interests of climate change mitigation. This research employs the ‘multi-level perspective’ (MLP) (Geels 2011), which analyses systems change from the level of ‘landscapes’, ‘regimes’ and ‘niches’. As an analytical framework, it is concerned with the way in which incumbent regimes lose stability and offers a heuristic device for narrative exploration (Smith, Voß, and Grin 2010). As previously explored in South Africa's case (Baker, Newell, and Phillips 2014), such a framing permits an inquiry into the relationship between entrenched coal-fired interests at the ‘regime’ level and emerging ‘niches’ in renewable electricity generation. While the regime is broadly defined here as South Africa's coal-fired, publicly-financed, state-controlled electricity sector, the niche involves an evolving cluster of renewable energy IPPs in which foreign companies and investors play a significant role. Both of these levels interact with and are backed by stakeholders and events at the ‘landscape’ level which for the purposes of this study include: pressures of climate change mitigation; developments in the international renewable energy market; norms of international project finance; and the increasing financialisation of resource-based conglomerates, in turn embedded within the regime as coal miners and energy-intensive users.

While the socio-technical transitions literature is useful for its analysis of technological and systems change, there have been calls to respond to the literature's inadequate consideration of political economy and power relations (Meadowcroft 2011; Goldthau and Sovacool 2012). This paper responds to this call and in turn challenges technocratic approaches to energy policy as identified by Büscher (2009) that fail to integrate nationally specific path dependencies and historical contingencies. Crucially, the framework put forward here allows for an exploration of the embedded nature of South Africa's electricity sector within its MEC and the role of mining and manufacturing industries, the utility, different government ministries, political and economic elites and international interests who hold a stake in or benefit from the sector in some way. An analysis of power can further be enriched by contributions from ecological modernisation, as it has been applied to the unique case of South Africa's energy sector (Long and Patel 2011).

In a critique of the MLP, Lawhon and Murphy (2011, 10) assert that it focuses too much ‘on the rules governing regimes – and not on who creates and benefits from them’. Building on this by bringing in Laswell's (1950) description of the politics of policy making as ‘who gets what, when and how’, this paper is motivated by the questions: Whose power plant gets connected to the electric grid, and who has control over the resources and the technology that supply the power plants? Who benefits on the demand side from the electricity that is generated? Who controls the transmission grid? Who has influence in the policy-making arena? And in what way? Such questions further allow us to consider the role of the state in facilitating the ability of competing fractions of capital to either reproduce their power at the level of the regime, or gain access to it. In socio-technical transitions terms, in the case of South Africa's electricity sector, these fractions can broadly be aligned with coal-mining and energy-intensive interests at the level of the ‘regime’ and renewable energy interests at the level of the ‘niche’. This can further be related to Fine and Rustomjee's (1996, 25) broader assertion that:

the history of the South African economy can in part be understood as the simultaneity of two processes: a shifting and complex short-term resolution of conflicts of capitalists’ interests and a longer-term integration and interpenetration of those capitals as they became increasingly large-scale and diversified. In both processes the state has played a central, mediating role.

The socio-technical transitions literature's examination of energy systems has generally focused on OECD countries, particularly Europe. Its consideration of low- and middle-income countries whose economy is predicated on natural resource extraction and/or heavy manufacturing within the context of a globalised and financially interdependent world is therefore limited (Lawhon and Murphy 2011, 10). In addition, much of the socio-technical transitions literature contains an implicit assumption that ‘radical green niches’ (Smith, Voß, and Grin 2010, 445) will automatically result in concomitant human co-benefits and the realisation of social equity, or in other words that a low-carbon transition will automatically be ‘just’. Such a perspective can overlook issues such as the role of labour, the social consequences of energy exploitation and infrastructure development, regardless of whether it is high or low carbon, and access to energy for the poor. Recent contributions that have addressed the global challenge of bringing about a transition that is at once ‘just’ and ‘low carbon’ can therefore be integrated here (COSATU 2012; Newell and Mulvaney 2013). Swilling and Annecke (2012) assert that a ‘just transition’ must be based on a mode of production that is not dependent on resource depletion and environmental degradation, and tackles global socio-economic inequalities in terms of consumption and access to power. Such a transition will require ‘deep structural changes’ with an approach to governance that is about minimisation as well as restoration, reconstruction and redistributive justice.

Minerals–energy complex: defining the regime

The MEC is the main contributor to the political economy approach of this paper, itself informed by theoretical debates current at its conception, including Marxist value theory, the theory and practice of developmental states and the military–industrial complex (Fine 2008, 1). Founded on intrinsic links between state corporations and private capital and the country's complex legacy of apartheid, it provides both a description of the nature of production and consumption in South Africa's economy organised in and around the energy and mining sectors and associated sub-sectors of manufacturing, and a theoretical framework for analysing power relations and key networks in the country's political economy (Freund 2010; Padayachee 2010).

The MEC as central to the socio-technical ‘regime’, referred to above, lies at the ‘core of the South African economy, not only by virtue of its weight in economic activity but also through its determining role throughout the rest of the economy’ (Fine and Rustomjee 1996, 5). Referring to a system of accumulation dating back to the 1870s, the MEC is central to the country's historical dependence on cheap coal and cheap labour along racially oriented divisions for cheap electricity. Such a system has in turn has served national economic dependence on core mining and minerals-beneficiation sectors, and the interests of export-oriented industry.

The MEC in its earlier stages consisted of the interrelationship between coal, electricity and gold mining, which later expanded into ‘more complex relationships between mining, electricity, [minerals] beneficiation and crude oil- and coal-based petrochemicals industries’ (Marquard 2006, 67). The historical influence of a small number of large resource-based conglomerates over policy, now internationalised with privileged access to cheap energy, tax breaks and infrastructure, is central to the MEC (Roberts 2007, 20), with Anglo American Corporation particularly dominant within this (Innes 1984). These sectors continue to be incredibly influential over the state and direction of the economy and ‘have been attached institutionally to a highly concentrated structure of corporate capital, state-owned enterprises and other organisations such as the Industrial Development Corporation (IDC) which have themselves reflected underlying structure and balance of economic and political power’ (Fine 2007, 11). Meanwhile, ‘new features’ (Ibid., 2) of the MEC that have developed in the post-apartheid era include: the development of a finance-led system of accumulation, now constituting 20% of GDP but failing to contribute to domestic investment (Fine 2012); increasing levels of capital flight and disinvestment and the often illegal expatriation of domestic capital (Ashman, Fine, and Newman 2011); and the development of Black Economic Empowerment companies (Tangri and Southall 2008).

A key stakeholder of the MEC is South Africa's state-owned, vertically integrated monopoly Eskom, which has been the sole transmitter of electricity via the country's high-voltage transmission grid, generating 96% of national electricity and responsible for 60% of distribution.2 According to Hallowes and Munnik (2007, 34), Eskom ‘has been at the centre of mega-project deals since the 1990s, offering the cheapest electricity in the world to new aluminium and steel plants’. The utility's largest 36 customers consume over 40% of the energy, of which BHP Billiton's aluminium smelters such as Hillside in South Africa and Mozal in Mozambique consume 5% of the country's 40,000 MW capacity (Creamer 2011a). By comparison, 30% of the country's population still do not have access to electricity, particularly in rural areas, and disconnection rates have risen in recent years (IDASA et al. 2010). Despite the free basic electricity tariff of 50 KWh per month, millions of low-income houses do not have enough regular income to buy enough electricity, even if they may be grid-connected (McDonald 2009, 16).

Another key player in the MEC that best illustrates the economic dominance of large-scale corporate capital is the country's coal industry, which currently supplies coal for 93% of the country's electricity generation. While electricity has been governed by the public monopoly Eskom, approximately 80% of the country's coal supply is controlled by five private monopolies: Anglo American Corporation, Exxaro, BHP Billiton, Xtrata and Sasol. These large multinational resource conglomerates have evolved from apartheid's six ‘axes of capital’ (Fine and Rustomjee 1996, 96–118). While Eskom is their biggest customer for coal supply, they in turn are amongst Eskom's biggest customers for electricity. They wield considerable influence over the utility with regards to setting the terms of coal supply (Eberhard 2011) and also have significant influence over policies governing the electricity generated by that coal (McDaid, Austin, and Bragg 2010).

In addition to cheap electricity, the country's century-old migrant labour system as a key input to South Africa's MEC still stands, and is emerging as a crisis for the regime. At the end of 2012, the country saw ‘the most explosive wave of strikes since the end of apartheid’ (Ashman and Fine 2012), following the massacre of 34 Lonmin platinum workers by police at a mine in Marikana. It is clear from this that the state has failed to uphold powerful resource conglomerates to account for meeting adequate labour standards in accordance with the Minerals and Petroleum Resources Development Act. Ashman and Fine (2012) surmise that ‘Marikana epitomises the MEC of today, reflecting both the economic and social failings of post-apartheid development, and the fragmentation, oppression and eruption of dissent to which it has led’.

The regime in crisis? Supply and demand

It can be argued that South Africa's electricity generation supply-side shortages which resulted in rolling blackouts and mine closures across the country in 2008 represented a crisis for the MEC, and a window of opportunity for the renewable energy niche. Following a period of surplus capacity3 since the mid 1980s, by 2008 the reserve margin fell to 6% (IBRD and Eskom Holdings Limited 2010, 11)4 with threats of further load shedding. Since 2005 Eskom has been facing a funding crisis and struggling to build an additional 17,000 MW of generation capacity by 2018 (Eskom 2011, 61). While this funding crisis was used to justify a controversial $3 billion loan from the World Bank as a ‘lender of last resort’ for the 4800 MW Medupi coal-fired power plant in 2010, climate change mitigation requirements have also challenged the country's coal-fired growth. In particular in 2009, President Jacob Zuma committed to reducing his country's greenhouse gas emissions by 34% by 2020 and 44% by 2025, contingent on financial support and technological transfer. Following year-on-year tariff hikes since 2009, in 2011 Canada replaced South Africa as the world's cheapest electricity-producing country, which is now in 11th place globally with an average cost of electricity at 8.55 US cents per kWh (Njobeni 2012). Reasons for this crisis, which have been explored in depth elsewhere (Steyn 2006; Eberhard 2011) and go beyond the scope of this paper, involve a legacy of historically entrenched, political, economic and technological factors.

In the light of this crisis, potential renewable energy developers argued for a feed-in tariff to incentivise large-scale renewable energy in order to tackle the gap in generation capacity at the same time as assisting the country to meet its climate change commitments. This feed-in tariff, eventually transferred to a bidding process under the RE IPPPP, is discussed below. Its allocation was included in the country's integrated resource plan for electricity, now discussed.

Plans for the significant diversification of South Africa's electricity mix, which includes over 20% of renewable energy in terms of installed capacity, are set out in the country's Integrated Resource Plan (IRP), written by Eskom and promulgated by the Department of Energy (DoE) in 2011. Based on a doubling of national electricity demand to 454 TWh, this plan implies an increase in generation capacity from approximately 41,000 MW to 90,000 MW by 2030.The IRP committed to a projected increase in coal-fired power, a potential nuclear fleet and the introduction of 23,559 MW of grid-connected, largely privately generated renewable energy (of which 9200 MW wind, 8400 MW photovoltaic (PV) and 1200 MW concentrated solar power (CSP)). The introduction of renewable generation was celebrated in some arenas for diversifying the country's electricity mix, given that the proportion of coal in the overall electricity mix decreased from 85 to 46%. However, as discussed elsewhere (Baker, Newell, and Phillips 2014), in absolute terms coal would increase from 34,952 to 41,071 MW. While recent revisions to this plan released by the DoE in a draft at the end of 2013 and under public comment at the time of writing have seen a downward adjustment in the demand forecast, coal is still set to remain the dominant energy source. The draft's proposed revisions include: an overall decrease in capacity by 6600 MW; a reduced contribution from coal (from 6250 MW to 2450 MW); an increased contribution from solar PV (from 8400 MW to 9770 MW) and CSP (from 1200 to 3000 MW); and a reduced contribution from wind (from 9200 MW to 4360 MW). The draft also suggests further lack of clarity over the proposed nuclear fleet and a potential increased role for gas.

Despite the DoE's previous resistance to the introduction of renewable energy (Baker 2011), the IRP illustrates how the South African government has succeeded in moderating conflict between the coal-generated ‘regime’ and emerging renewable ‘niche’, by allowing for growth in the former and introduction of the latter, thereby perpetuating what Jessop (1990, 27) refers to as ‘the dominant mode of production’.

The emerging niche

South Africa's renewable energy niche was facilitated by the RE IPPPP, launched by the DoE in August 2011. In the first instance, this allowed for the entry of 3725 MW of renewable electricity generation into the country's electricity grid by 2016. An additional procurement of 3200 MW of generation capacity was later declared by the energy minister in December 2012. Successful projects will sell electricity to Eskom's grid under a 20-year, government-backed power purchase agreement. The announcement of the first and second round of successful projects, the key focus of this paper, took place in December 2011 and May 2012, with the third round of bidders announced in October 2013 (see Table 1). A fourth bid submission date is set for August 2014. All projects must begin commercial operation before the end of 2016 at the latest and a number of projects are already connected to the grid as of January 2014.

| Technology | MW awarded, Round 1 (Dec. 2011) | No. of projects awarded, Round 1 (May 2012) | MW awarded, Round 2 | No. of projects awarded, Round 2 | MW awarded, Round 3 (Oct. 2013) | No. of projects awarded, Round 3 | Total MWs awarded, Rounds 1–3 | Total projects awarded, Rounds 1–3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solar PV | 631.5 | 18 | 417.1 | 9 | 435 | 6 | 1484 | 33 |

| Wind | 633.99 | 8 | 562.4 | 7 | 787 | 7 | 1983 | 22 |

| Solar CSP | 150 | 2 | 50 | 1 | 200 | 2 | 400 | 5 |

Source: Adapted from http://www.ipprenewables.co.za.

Initiated in 2007 in the form of a feed-in tariff in what can be described as a ‘niche’ policy intervention by the National Energy Regulator in 2007 ‘acting beyond its mandate’, according to one energy analyst, for some years the process faced opposition from within the regulator itself, from the DoE and a general resistance within Eskom towards renewable energy. This, despite increasing impatience from renewable energy IPPs waiting to construct their projects and feed into the national grid. Throughout its negotiation, the process met with numerous delays due to disagreements over the appropriate regulatory framework, mistrust of renewable energy from some factions of government and industry, perceived political and financial risks, and a last-minute replacement of the feed-in tariff with a competitive bidding system (Baker, Newell, and Phillips 2014). Having gained irreversible traction and subject to unavoidable international pressure, the process was eventually taken over by the DoE and the Treasury in November 2010 (Baker 2012). Following global trends, the greatest interest in South Africa's RE IPPPP originally came from the wind industry, although since 2008, solar PV technologies have gained ground as their international market price and capital costs have dropped markedly (REN 21 2011).

Following a tender system based on competitive bidding, potential project developers are invited to bid for a renewable energy contract (Mendonça, Jacobs, and Sovacool 2010, 174). Tender documents are subject to a fee of R15,0005 and thus have not been accessed for this research. In South Africa, developers must firstly demonstrate how they will fulfill socio-economic development criteria and secondly offer a price below a certain cap. Bids are scored 70% on price and 30% on socio-economic development criteria which include job creation, participation of historically disadvantaged individuals, protection of local content, local manufacturing, rural development, community involvement and skills development (Creamer 2011b). The bid that meets the requirements at the lowest price wins the contract. Eskom is excluded from bidding with its role confined to the buyer of power and connection of the projects to the grid. It is estimated that the RE IPPPP will add an average incremental cost of $660 million to South Africa's yearly electricity bill up to 2044, which will be borne by electricity consumers under the ‘multi-year price determination’ and tariff hikes (Ibid.).

Wind projects were subject to a 25% local content requirement in the first two bidding rounds, while in the third round this increased to 45%, necessarily implying blade and turbine contributions (de Vos 2013). Two manufacturing plants are now being set up to build wind towers for RE IPPPP projects in order to meet local content requirements: DCD Towers in the Coega Industrial Development Zone to supply towers to Nordex and Vestas (Dodd 2013) and Gestamp Renewable Industries in Atlantis, near Cape Town.6 However, in global terms South Africa is behind the curve of a relatively mature and consolidated global wind industry, to which there are significant barriers to entry in light of increasingly sophisticated technology, and reluctance amongst leading turbine manufacturers to license their turbine technologies, particularly to developing countries (Lewis and Wiser 2007, 1846–1847). World Trade Organization regulations could also pose an obstacle, for instance to the ability of South Africa to tax the import of foreign wind turbines in order to meet local content requirements. That said, the ‘green economy’ is a stated priority for the government as outlined in a number of government documents, including the Department for Trade and Industry's Industrial Policy Action Plan (DTI 2011), the Economic Development Department's New Growth Path (EDD 2011) and the 2013 National Development Plan (NPC 2013).

Wind rush

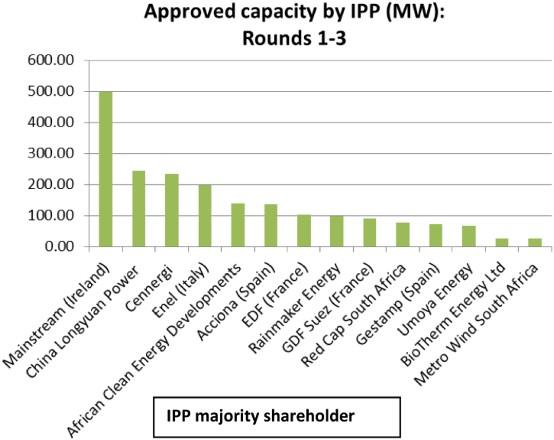

Within the context of recent policy developments discussed above, this section examine South Africa's nascent wind industry as a subsector of the renewable energy niche, which is being developed by IPPs under the RE IPPPP. IPPs tend to have a complex structure of project ownership involving various combinations of multi-national, national and community players. Many IPPs include a foreign parent company as the major shareholder which has set up a South African subsidiary, and/or a foreign company acting in joint venture with a South African company. Company origins include: Germany, Denmark, Ireland, Spain, France and Italy as well as the emerging markets of India and China (see Figure 1). In the case of projects approved under Rounds one and two of the RE IPPPP, debt finance has been provided by South Africa's five main commercial banks. Equity investors include a mix of private equity firms, development finance institutions, BEE partners and community shareholders often funded by the IDC.

Approved capacity by IPP (MW), RE IPPPP, Rounds one to three. Source: Author's own compilation from publicly available sources as of January 2014.

While technology supply to South Africa's wind industry is central to the development of national priorities of local content and localisation, it has remained the domain of foreign actors given that, to date, IEC7 certification requirements would preclude the ability of South African companies from entering the supply chain. In addition, debt finance requirements from risk-adverse national banks would also prohibit ‘unproven’ technology suppliers that lack the appropriate track record and reputation. Danish Vestas has had a representative in the country for more than a decade and under Rounds one and two of RE IPPPP was in the lead as preferred supplier and engineering, procurement and construction contractor for five projects, with a total capacity of 465 MW. German Nordex followed with 26%.8 However, rapidly shifting trends in international wind technology manufacturing see early entrants to the global industry from Denmark, Germany, Spain and the US now competing with emerging market companies (UNEP and Bloomberg New Energy Finance 2011). As India and China's burgeoning domestic manufacturing industries in wind and solar PV continue to seek export markets (Walz and Delgado 2012), this is inevitably playing out in South Africa (see Figure 2). This analysis of wind industry stakeholders reveals how competition between transnational giants based in ‘core’ nations, which has long been a feature of South Africa's industrial development (Makgetla and Seidman 1980), is now playing out in its nascent renewable energy industry with core nations now including emerging market companies such as India and China.

Wind capacity by technology provider, RE IPPPP, Rounds one and two. Source: Author's compilation from publicly available sources as of 1 October 2013.

Suzlon Energy Ltd, India's largest wind turbine manufacturer (GWEC 2010, 5), set up an office in late 2010, appointing former managing director of City Power, Johannesburg's municipal electricity distributor, Silus Zimu as its in-country CEO. This was described as a political appointment due to Zimu's assumed access to power and influence within the ruling party. In May 2011, Suzlon was the first technology supplier in South Africa to make public a supply agreement for 76 turbines for African Clean Energy Development's 135 MW Cookhouse project in the Eastern Cape. Suzlon was also to have supplied turbines for Cennergi's 140 MW Amakhala Emoyeni project in the Eastern Cape under an Engineering Procurement Construction agreement but was replaced by German Nordex in the months prior to financial close in June 2013, with concerns over the company's financial bankability cited as a reason for this switch (Dodd 2013).

Infrastructure development in South Africa is uniquely characterised by the Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) requirement as a precondition to obtaining a generation licence and qualifying as a preferred bidder. Given that BEE has primarily resulted in the enrichment of an unproductive black elite with limited trickle-down potential, rather than a tool of genuine socio-economic transformation (Hamann, Khagram, and Rohan 2008; Mbeki 2011), how BEE plays out in the renewable energy space is a critical national issue. Details in the public regarding the integration of BEE companies within South Africa's nascent renewable energy industry are scarce but emerging. One example is Spain's Gestamp Wind, which will develop the Noblesfontein wind farm in partnership with South Africa's SARGE (South African Renewable Green Energy) and BEE company Shanduka, a leading black-owned investment holding company established in 2000 by the country's leading businessman Cyril Ramaphosa (Fin 24 2012).

In 2010, a number of civil society and labour representatives expressed fears that the introduction of IPPs would create a private monopoly driven largely by a white elite backed by international energy giants. The nascent industry was also criticised in the press for being predominantly white and male (Salgado 2010), reflected in the membership of the South African Wind Energy Association's board, which until May 2011 consisted almost exclusively of white men, though this has since diversified. More critically, in 2010 one civil society representative interviewed referred to the industry as consisting largely of ‘white wind capitalists’. This can be related to Lazar's (1987, unpublished, in Fine and Rustomjee 1996, 149) reference to ‘land capitalists’ to describe a small number of powerful farmers in the 1960s who controlled a large section of the country's agriculture under apartheid.

Unions expressed concern that the introduction of renewable energy was being carried out by profit-making interests amidst fears that it would affect job security. The Congress of South African Trade Unions’ (COSATU's) Policy Framework on Climate Change (COSATU 2012, 18) states that ‘capitalist accumulation has been the underlying cause of excessive greenhouse gas emissions, and therefore global warming and climate change’, and that ‘a new low carbon development path is needed which addresses the need for decent jobs and the elimination of unemployment’. COSATU's principles for this just transition are echoed in Cock (2011, 239), who states that ‘we also have to ensure that the development of new, green industries does not become an excuse for lowering wages and social benefits. New environmentally–friendly jobs provide an opportunity to redress many of the gender imbalances in employment and skills’.

Similarly, in February 2012 the National Union of Metal Workers of South Africa expressed concern that that workers and communities would be ‘forced to pay the costs of the [renewable energy] sector's expansion’ (Algoa FM 2012). At the Union's annual conference in 2012, its president, Cedric Gina, asked: ‘is this another capitalist grab to enrich a few?’ He continued, ‘for whom is the renewable energy being produced? Is it for big corporations who get the electricity at a discount or is it to give access to those who presently do not have access?’ (SAPA 2012). Andre Otto of the South African Wind Energy Programme9 endorsed this:

the unions (in South Africa) should be concerned. In Denmark the first developers of wind turbines were farmers – then it became big. The question here (in South Africa) is how we bring communities (into the fold). We need to take (the development) to those communities – to see how we can assist them. (In Aboobaker 2012)

While limited research has been carried on how labour is being incorporated into and prioritised within the emerging renewable energy sector, this issue is crucial if future tragedies such as Marikana are to be avoided. Early anecdotal evidence suggests that in the case of some projects, expectations within communities have been raised unrealistically over the number of jobs that will be created and how long for.

From Exxaro to Cennergi: ‘hedging bets’

In terms of the political economy of socio-technical transitions, Exxaro offers a fascinating case study of a powerful MEC stakeholder and regime incumbent engaging in niche-level developments. It is South Africa's second largest coal producer at approximately 45.2 million tonnes of coal per annum and its carbon footprint makes up 1% of the country's emissions at approximately 2.7 million tonnes per annum (MoneyWeb 2011). Formed in 2006, its creation stems from the former steel parastatal Iscor, set up in 1928 and privatised in 1989. Having established a clean energy forum in 2007, by 2011 the company agreed a 50:50 joint venture with a subsidiary of India's Tata Power, Khopoli Investments, which led to the formation of the company Cennergi in April 2012. Cennergi has a separate board and governance system, of which Exxaro is the primary shareholder (Creamer 2012), and is headed by a former Exxaro employee.

Exxaro is the largest black-owned company listed on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange and is currently 56% BEE-controlled. It has considerable political reach. As one energy analyst stated in May 2010:

they have access to decision-makers that new [renewable energy] developers do not and influenc[e] access within the ruling party, all departments, and at all different levels as well as many personal relationships. Exxaro are hugely influential, are making an effort to collaborate with the government on sustainability and have a different approach than the average capitalist.

Exxaro explained that its move into renewables was driven by the need to ‘become carbon neutral’ and ‘thrive in a low-carbon economy’ (Exxaro 2011) in light of rising costs and increasing scarcity of electricity. One mining energy expert explained that a renewable energy business could help mitigate anticipated future trade barriers that a carbon-sensitive market may place on the company's coal exports and other South African carbon-intensive goods. As the company's executive general manager of business growth, Ernst Venter, explained, ‘for every tonne of coal that we want to export, we want to be able to place a green stamp on that – if you can call it that’ (in MoneyWeb 2011). With ambitious plans for growth in South Africa and the region, Cennergi's two projects in the Eastern Cape selected under Round two constituted the largest amount of MW awarded for wind energy under the first and second bidding rounds of RE IPPPP, with a total capacity of 235 MW. That said, its lead status has since diminished following the announcement of preferred bidders under Round three (see Figure 1). It can be argued that Exxaro's activities represent a strategic attempt to reproduce its power and influence within the renewable energy niche. Thus far the company is unique within its minerals and energy giant peer group in galvanising its traditional resources to renewable ends under the RE IPPPP. However, as the sole supplier of coal to the 4800 MW Medupi coal-fired power plant, for which it is undertaking the massive development of untapped deposits in the Waterberg, the company's core business in coal and minerals clearly remains fundamental. Seemingly it has seized the opportunity to mitigate its core activities and thereby reproduce its dominance within the context of shifting regime trends. One mining industry expert explained that: ‘Exxaro has worn two hats. It is lobbying for the cheapest possible electricity which comes from coal but is also preparing to get involved in a new energy future. It is hedging its bets’.

Conclusion

In analysing the extent to which the introduction of privately generated renewable energy into the country's coal-dominated electricity mix constitutes a ‘low-carbon transition’ in South Africa's MEC, this paper has found that a number of shifts and new features are evident. Significantly, the country's electricity sector is subject to notable change, which follows on from a supply-side crisis exacerbated by, though by no means limited to, international environmental pressures, increasing coal costs and rising tariffs. Though no match for incumbent MEC stakeholders, renewable energy IPPs have capitalised on this crisis and acquired a certain level of access within the coal-dominated regime in terms of access to the grid, policy influence, project development and financial subsidies under the RE IPPPP. In addition to an influx of foreign and international players whose impact on skills development and the long-term socio-economic benefits of industry in South Africa has yet to be determined, the renewable energy niche has also incorporated a major MEC incumbent in the form of Exxaro.

While renewable IPPs are contributing to a diversification in the national electricity mix, their introduction still contributes to an electricity-intensive model predicated on an increase in demand, with issues of affordability for low-income households unresolved. Renewable energy developments are paralleled by the construction of large-scale, coal-fired power backed by large volumes of national and international public finance, in addition to the potential, though still uncertain, introduction of nuclear power. Significantly, proposed changes in electricity apply to the generation mix but not to consumption, which is dominated by the country's energy-intensive users. The IRP's trajectory is based on a significant increase in mining and minerals beneficiation by 2030, with a concomitant expansion of electricity generation. Therefore, despite the emergence of new players and evolving configurations of institutions and technologies in the energy sector, the MEC is still a key driver of policy decisions in electricity, and still represents an integral relationship between the state and private capital and a ‘core set of activities around mining and energy’ (Fine 2008, 1). The ‘uniquely electricity intensive’ nature (Fine and Rustomjee 1996, 8) of South Africa's economic growth strategy remains unchanged. In addition, the centralised grid system to which they will connect remains largely undisturbed and so it can be argued that these ‘niche’ innovations in renewable electricity generation cannot be considered ‘radical’ (Geels 2011).

A further feature of the MEC is that Eskom's monopoly stronghold over electricity generation and transmission appears to be under challenge. The introduction of IPPs into the electricity grid raises further questions as to whether the introduction of privately generated electricity is a break with the past which will lead to the eventual dismantling of the utility's control over national electricity generation and transmission. It is perhaps an illustration of Fine's (2008, 9) claim that South Africa's energy-intensive users are no longer able ‘to have their interests met by the state’ or McDonald's (2009, 20) finding that the traditional MEC model of ‘big state negotiating with big capital is changing’ in favour of a ‘fragmented and rescaled state negotiating with more globally dispersed capital, in many different sectors with new technical demands’. With that in mind, it can be further argued that an interdependence of networks and institutions between South Africa's coal-based ‘regime’ and renewable ‘niche’ is emerging despite evident competition between these two sites. Power is located in linkages as much as within institutions as different fractions of capital, facilitated by government support and international finance, jostle for access to the grid.

This paper has raised a number of key areas for further research with regards to the role of renewable energy generation within the MEC. These include: how the solar PV and solar CSP industries are developing as key players in the renewable electricity generation sector parallel to wind; how the role of BEE is integrating within a new renewable industry and whether it will avoid elite capture by linking powerful political leaders with financial interests as has been witnessed in the mining industry; the way in which foreign and international energy companies are involved in project development, finance and investment, technology supply and service contracts; and the nature of national and international supply chains for renewable energy technology in South Africa.

A final consideration is whether South Africa's socio-technical transition is just, in addition to low carbon. As these projects will connect directly to the electricity grid, they will fail to reach the 30% of the population that is not connected. The extent to which these projects may bring about the socio-economic benefits required in the bidding criteria is as yet unclear and an area for further research. Furthermore, following Moe (2010, 1732), it is possible that some renewable energy IPPs may themselves become vested interests in parallel to traditionally entrenched incumbents and in turn become a new form of accumulation that will fail to tackle energy poverty and will reinforce historical inequalities. Without a fundamental reorientation of the country's coal-fuelled, consumption-led economy in which cheap black labour remains a key input and, significantly, the demands at the national and international level that fuel this, any meaningful just and low-carbon socio-technical transition will be hard to achieve.