- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Interventions to provide culturally-appropriate maternity care services: factors affecting implementation

Read this article at

Abstract

Background

The World Health Organization recently made a recommendation supporting ‘culturally-appropriate’ maternity care services to improve maternal and newborn health. This recommendation results, in part, from a systematic review we conducted, which showed that interventions to provide culturally-appropriate maternity care have largely improved women’s use of skilled maternity care. Factors relating to the implementation of these interventions can have implications for their success. This paper examines stakeholders’ perspectives and experiences of these interventions, and facilitators and barriers to implementation; and concludes with how they relate to the effects of the interventions on care-seeking outcomes.

Methods

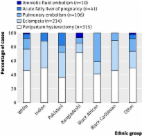

We based our analysis on 15 papers included in the systematic review. To extract, collate and organise data on the context and conditions from each paper, we adapted the SURE (Supporting the Use of Research Evidence) framework that lists categories of factors that could influence implementation. We considered information from the background and discussion sections of papers included in the systematic review, as well as cost data and qualitative data when included.

Results

Women’s and other stakeholders’ perspectives on the interventions were generally positive. Four key themes emerged in our analysis of facilitators and barriers to implementation. Firstly, interventions must consider broader economic, geographical and social factors that affect ethnic minority groups’ access to services, alongside providing culturally-appropriate care. Secondly, community participation is important in understanding problems with existing services and potential solutions from the community perspective, and in the development and implementation of interventions. Thirdly, respectful, person-centred care should be at the core of these interventions. Finally, cohesiveness is essential between the culturally-appropriate service and other health care providers encountered by women and their families along the continuum of care through pregnancy until after birth.

Conclusion

Several important factors should be considered and addressed when implementing interventions to provide culturally-appropriate care. These factors reflect more general goals on the international agenda of improving access to skilled maternity care; providing high-quality, respectful care; and community participation.

Related collections

Most cited references27

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

'Weighing up and balancing out': a meta-synthesis of barriers to antenatal care for marginalised women in high-income countries.

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Inequalities in maternal health: national cohort study of ethnic variation in severe maternal morbidities

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found