- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Knowledge and Practices Regarding Safe Household Cleaning and Disinfection for COVID-19 Prevention — United States, May 2020

research-article

Radhika Gharpure , DVM

1

,

2

,

,

Candis M. Hunter , PhD

1 ,

Amy H. Schnall , MPH

3 ,

Catherine E. Barrett , PhD

1 ,

Amy E. Kirby , PhD

1 ,

Jasen Kunz , MPH

1 ,

Kirsten Berling , MPH

1 ,

Jeffrey W. Mercante , PhD

1 ,

Jennifer L. Murphy , PhD

1 ,

Amanda G. Garcia-Williams , PhD

1

12 June 2020

Read this article at

There is no author summary for this article yet. Authors can add summaries to their articles on ScienceOpen to make them more accessible to a non-specialist audience.

Abstract

On June 5, 2020, this report was posted online as an MMWR Early Release.

A recent report described a sharp increase in calls to poison centers related to exposures

to cleaners and disinfectants since the onset of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)

pandemic (

1

). However, data describing cleaning and disinfection practices within household settings

in the United States are limited, particularly concerning those practices intended

to prevent transmission of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. To provide

contextual and behavioral insight into the reported increase in poison center calls

and to inform timely and relevant prevention strategies, an opt-in Internet panel

survey of 502 U.S. adults was conducted in May 2020 to characterize knowledge and

practices regarding household cleaning and disinfection during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Knowledge gaps were identified in several areas, including safe preparation of cleaning

and disinfectant solutions, use of recommended personal protective equipment when

using cleaners and disinfectants, and safe storage of hand sanitizers, cleaners, and

disinfectants. Thirty-nine percent of respondents reported engaging in nonrecommended

high-risk practices with the intent of preventing SARS-CoV-2 transmission, such as

washing food products with bleach, applying household cleaning or disinfectant products

to bare skin, and intentionally inhaling or ingesting these products. Respondents

who engaged in high-risk practices more frequently reported an adverse health effect

that they believed was a result of using cleaners or disinfectants than did those

who did not report engaging in these practices. Public messaging should continue to

emphasize evidence-based, safe practices such as hand hygiene and recommended cleaning

and disinfection of high-touch surfaces to prevent transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in household

settings (

2

). Messaging should also emphasize avoidance of high-risk practices such as unsafe

preparation of cleaning and disinfectant solutions, use of bleach on food products,

application of household cleaning and disinfectant products to skin, and inhalation

or ingestion of cleaners and disinfectants.

Survey questions were administered by Porter Novelli Public Services and ENGINE Insights

on May 4, 2020, through PN View: 360,* a rapid turnaround survey that can be used

to provide insights into knowledge and practices of targeted audiences. This opt-in

Internet panel survey was administered to 502 U.S. adults aged ≥18 years using the

Lucid platform (

3

); panel members who had not taken a survey in the previous 20 waves of survey administration

were eligible to participate. Quota sampling and statistical weighting were employed

to make the panel representative of the U.S. population by gender, age, region, race/ethnicity,

and education. Respondents were informed that their answers were being used for market

research and could refuse to answer any question at any time. No personally identifying

information was included in the data file provided to CDC.

†

Survey questions asked about general knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to

use of household cleaners and disinfectants

§

and about specific information regarding cleaning and disinfection strategies for

prevention of SARS-CoV-2 transmission. Weighted response frequencies were calculated

using SAS statistical software (version 9.4; SAS Institute). Because respondents were

recruited from an opt-in panel rather than by probability sampling, no inferential

statistical tests were performed.

¶

Differences were noted when a difference of ≥5 percentage points was found between

any estimates being compared.

The median age of respondents was 46 years (range = 18–86 years), and 52% of respondents

were female. Overall, 63% of respondents were non-Hispanic white, 16% were Hispanic

(any race), 12% were non-Hispanic black, and 8% were multiracial or of other race/ethnicity.

Respondents represented all U.S. Census regions,** with 38% from the South, 24% from

the West, 21% from the Midwest, and 18% from the Northeast.

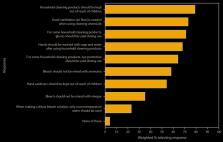

Participants had limited knowledge of safe preparation of cleaning and disinfectant

solutions (Figure 1). Overall, 23% responded that only room temperature water should

be used for preparation of dilute bleach solutions, 35% that bleach should not be

mixed with vinegar, and 58% that bleach should not be mixed with ammonia. In comparison,

a higher percentage of respondents had knowledge about use of recommended personal

protective equipment: 64% responded that eye protection was recommended for use of

some cleaners and disinfectants, and 71% responded that gloves were recommended for

use. Similarly, 68% responded that handwashing was recommended after using cleaners

and disinfectants and 73% that adequate ventilation was recommended when using these

products. Regarding safe storage of cleaners, disinfectants, and hand sanitizers,

79% of respondents said that cleaners and disinfectants should be kept out of the

reach of children, and 54% that hand sanitizers should be kept out of the reach of

children.

FIGURE 1

Knowledge about safe use of cleaners and disinfectants,*

,

†

based on responses to an opt-in Internet panel survey

§

(N = 502 respondents) — United States, May 2020

* In response to the question ”Which of the following have you heard is true about

using household cleaning products (such as bleach or Lysol)?”; response options reflected

CDC recommendations for safe cleaning and disinfection. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/disinfecting-your-home.html.

† In survey questions, the term “cleaning” referred to using a cleaner or disinfectant

on surfaces or objects. Questions regarding storage of hand sanitizers were included

with questions regarding storage of cleaners and disinfectants.

§ Survey administered by Porter Novelli Public Services through PN View: 360; respondents

could select multiple responses to the question (all response options shown). Selection

of the response “none of these” was exclusive (i.e., respondents could not select

this response option in addition to other responses).

The figure is a horizontal bar graph indicating knowledge about safe use of cleaning/disinfectant

products in the United States, based on responses of 502 persons to an opt-in Internet

panel survey administered in May 2020.

Respondents reported engaging in a range of practices during the previous month with

the intent of preventing SARS-CoV-2 transmission (Figure 2). Sixty percent of respondents

reported more frequent home cleaning or disinfection compared with that in preceding

months. Thirty-nine percent reported intentionally engaging in at least one high-risk

practice not recommended by CDC for prevention of SARS-CoV-2 transmission (

2

), including application of bleach to food items (e.g., fruits and vegetables) (19%);

use of household cleaning and disinfectant products on hands or skin (18%); misting

the body with a cleaning or disinfectant spray (10%); inhalation of vapors from household

cleaners or disinfectants (6%); and drinking or gargling diluted bleach solutions,

soapy water, and other cleaning and disinfectant solutions (4% each).

FIGURE 2

Cleaning and disinfection practices in the previous month with the intent of preventing

SARS-CoV-2 infection,*

,

†

based on responses to an opt-in Internet panel survey

§

(N = 502 respondents) — United States, May 2020

* In response to the question “In the past month, which of the following cleaning

behaviors have you or a household member engaged in to prevent coronavirus?”

† In survey questions, the term “cleaning” referred to using a cleaner or disinfectant

on surfaces or objects.

§ Survey administered by Porter Novelli Public Services through PN View: 360; respondents

could select multiple responses to the question (nine of 11 possible response options

shown). Selection of the response “none of these” was exclusive (i.e., respondents

could not select this response option in addition to other responses).

The figure is a horizontal bar graph showing the cleaning and infection practices

employed by U.S. persons in the previous month with the intent of preventing SARS-CoV-2

infection, based on responses of 502 persons to an opt-in Internet panel survey administered

in May 2020.

One quarter (25%) of respondents reported at least one adverse health effect during

the previous month that they believed had resulted from using cleaners or disinfectants,

including nose or sinus irritation (11%); skin irritation (8%); eye irritation (8%);

dizziness, lightheadedness, or headache (8%); upset stomach or nausea (6%); or breathing

problems (6%). Respondents who reported engaging in at least one high-risk practice

more frequently reported an adverse health effect than did those who did not report

engaging in such practices (39% versus 16%).

Approximately half (51%) of respondents strongly agreed and 31% somewhat agreed that

they knew how to clean and disinfect their home safely. Similarly, 42% strongly agreed

and 35% somewhat agreed that they knew how to clean and disinfect their home to prevent

SARS-CoV-2 transmission. When asked who their most trusted sources of SARS-CoV-2-related

cleaning and disinfection information were, the top three responses were CDC (65%),

state or local health departments (49%), and doctors, nurses, or medical providers

(48%).

Discussion

This survey identified important knowledge gaps in the safe use of cleaners and disinfectants

among U.S. adults; the largest gaps were found in knowledge about safe preparation

of cleaning and disinfectant solutions and about storage of hand sanitizers out of

the reach of children. Mixing of bleach solutions with vinegar or ammonia, as well

as application of heat, can generate chlorine and chloramine gases that might result

in severe lung tissue damage when inhaled (

4

,

5

). Furthermore, exposures of children to hand sanitizers, particularly via ingestion,

can be associated with irritation of mucous membranes, gastrointestinal effects, and

in severe cases, alcohol toxicity (

6

). The risk of ingestion and consequent toxicity from improperly stored hand sanitizers,

cleaners, and disinfectants can also extend to pets (

7

).

Consistent with current guidance for daily cleaning and disinfection of frequently

touched surfaces (

2

), a majority of respondents reported increased frequency of cleaning in the home.

However, approximately one third reported engaging in high-risk practices such as

washing food products with bleach, applying household cleaning and disinfectant products

to bare skin, and intentionally inhaling or ingesting cleaners or disinfectants. These

practices pose a risk of severe tissue damage and corrosive injury (

8

,

9

) and should be strictly avoided. Although adverse health effects reported by respondents

could not be attributed to their engaging in high-risk practices, the association

between these high-risk practices and reported adverse health effects indicates a

need for public messaging regarding safe and effective cleaning and disinfection practices

aimed at preventing SARS-CoV-2 transmission in households.

COVID-19 prevention messages should continue to emphasize evidence-based, safe practices

such as frequent hand hygiene and frequent cleaning and disinfection of high-touch

surfaces (

2

). These messages should include specific recommendations for the safe use of cleaners

and disinfectants, including the importance of reading and following label instructions,

using water at room temperature for dilution (unless otherwise stated on the label),

avoiding mixing of chemical products, wearing skin protection and considering eye

protection for potential splash hazards, ensuring adequate ventilation, and storing

and using chemicals and hand sanitizers out of the reach of children and pets (

10

). Despite the knowledge gaps and high-risk practices identified in this survey, most

respondents believed that they knew how to clean and disinfect their homes safely;

thus, prevention messages should highlight identified gaps in knowledge about safe

and effective practices and provide targeted information using innovative communication

strategies (e.g., digital, social media) regarding safe cleaning and disinfection.

These messages about cleaning and disinfection practices for COVID-19 prevention can

be coordinated and disseminated through trusted sources of information such as national,

state, and local public health agencies and medical providers.

The findings in this report are subject to at least four limitations. First, although

survey responses were weighted to be nationally representative of U.S. demographics,

whether responses among this opt-in panel sample are truly representative of knowledge,

attitudes, and practices shared by the broader U.S. population is difficult to determine.

Second, social desirability bias might have affected responses, with some respondents

potentially overstating their perceived knowledge or underreporting engagement in

high-risk practices; thus, these findings might underestimate the risk for exposures.

Third, cross-sectional data captured in survey responses do not allow for direct attribution

of specific outcomes, such as adverse health effects, to specific knowledge gaps or

practices. Finally, responses were recorded at a single point in time and might not

reflect ongoing shifts in public opinion or cleaning and disinfection practices by

the public throughout the national COVID-19 response.

Efforts are ongoing to collect these data over time and to characterize knowledge

gaps and practices among specific demographic and geographic groups. These data will

allow for development and evaluation of further targeted messaging to ensure safe

cleaning and disinfection practices in U.S. households during and after the COVID-19

pandemic.

Summary

What is already known about this topic?

Calls to poison centers regarding exposures to cleaners and disinfectants have increased

since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

What is added by this report?

An Internet panel survey identified gaps in knowledge about safe preparation, use,

and storage of cleaners and disinfectants. Approximately one third of survey respondents

engaged in nonrecommended high-risk practices with the intent of preventing SARS-CoV-2

transmission, including using bleach on food products, applying household cleaning

and disinfectant products to skin, and inhaling or ingesting cleaners and disinfectants.

What are the implications for public health practice?

Public messaging should continue to emphasize evidence-based, safe cleaning and disinfection

practices to prevent SARS-CoV-2 transmission in households, including hand hygiene

and cleaning and disinfection of high-touch surfaces.

Related collections

Most cited references5

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Cleaning and Disinfectant Chemical Exposures and Temporal Associations with COVID-19 — National Poison Data System, United States, January 1, 2020–March 31, 2020

Arthur Chang, Amy Schnall, Royal Law … (2020)

- Record: found

- Abstract: not found

- Article: not found

The clinical toxicology of sodium hypochlorite

Robin Slaughter, Martin Watts, J Vale … (2019)

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Reported Adverse Health Effects in Children from Ingestion of Alcohol-Based Hand Sanitizers — United States, 2011–2014

Cynthia W Santos, Stephanie Kieszak, Alice Wang … (2017)