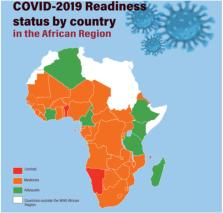

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak, which started in the Hubei province of China in 2019, has now spread to all continents, affecting 177 countries by March 27, 2020. 1 Successful efforts in containing the COVID-19 virus in Asia resulted in WHO declaring Europe as the epicentre of the disease on March 13. 2 Whether warmer temperatures will slow the spread of the COVID-19 virus, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has been a point of much speculation. This hypothesis has led some European countries to produce initial policies relying on decreased transmission rates during the summer months, 3 and the belief that African countries will face smaller epidemics than their European counterparts. However, no strong evidence base exists for such claims; SARS-CoV-2 might have simply arrived later to warmer countries. We used data from the COVID-19 data repository of the Johns Hopkins Center for Systems Science and Engineering (Baltimore, MD, USA) to plot the cumulative number of cases since the diagnosis of both the first patient and the first five patients by country, both in Europe and Africa (figure ). Although the first confirmed COVID-19 cases occurred later in west Africa than in Europe, once these first cases were confirmed in west Africa, the expansion in the number of confirmed COVID-19 was rapid. Of particular concern are Burkina Faso and Senegal, which saw sharp increases in the number of cases soon after the initial cases were confirmed in these countries. Cases in both countries might evolve in a similar way to what was observed in European countries with the most expansive epidemics (ie, Italy and Spain, where SARS-CoV-2 spread quickly after case number five was detected). Senegal also confirmed its first three cases of community transmission on March 21, 4 suggesting more cases in this country than the 119 confirmed on March 27. Figure Evolution of COVID-19 pandemic Curves show how the pandemic initially evolved in west African countries (continuous lines) compared with European countries (dashed lines) and other African countries (dotted lines): from the first case diagnosed in the country (A); and from the fifth case diagnosed in the country (B). Graphs were generated with data downloaded from the COVID-19 data repository of the Johns Hopkins Center for Systems Science and Engineering on March 23, 2020. COVID-19=coronavirus disease 2019. The impact of a similar epidemic as currently seen in Europe would be devastating in west Africa. Although some west African countries have measures in place from the 2014 Ebola epidemic, the region includes some of the poorest countries in the world (according to World Bank data, nine of the 25 poorest countries are in the region). In addition, many west African countries have poorly resourced health systems, rendering them unable to quickly scale up an epidemic response. Most countries in the region have fewer than five hospital beds per 10 000 of the population and fewer than two medical doctors per 10 000 of the population (based on WHO global health observatory data), and half of all west African countries have per capita health expenditures lower than US$50 (based on WHO global health expenditure data. In contrast, Italy and Spain have 34 and 35 hospital beds, respectively, per 10 000 of the population, 41 medical doctors per 10 000 of the population, and US$2840 and US$2506 per capita expenditure. Despite having young populations (old age is a major risk factor for severe forms of COVID-19 and mortality), some west African countries have rates of other risk factors similar to European countries. For instance, 27% of Gambians have hypertension 5 and 6% have diabetes. 6 We believe the epidemic has started later in west Africa than for other regions globally because of the limited international air traffic, rather than the climate conditions. Now that community transmission is ongoing in some countries, the amount of time to prepare an epidemic response is limited. Early identification of confirmed cases, swift contact tracing with physical isolation, community engagement, and health systems measures are all necessary to avert the potentially harmful consequences of an epidemic in the region. To conclude, early comparisons between the number of confirmed cases in the worst affected European countries and the west African countries with confirmed COVID-19 cases do not support the hypothesis that the virus will spread more slowly in countries with warmer climates. In the case of west Africa, a rapid acceleration in the number of cases could quickly overwhelm already vulnerable health systems. Swift action to control further spread of the virus, and to improve the response capabilities of affected countries in west Africa is therefore urgent.