INTRODUCTION

Disability services are considered an important factor that affects the academic life of disabled students. Many countries and universities around the world started to improve their disability services many years ago ( Madaus, 2011). The discussion on the issue of disability and students with disabilities has been raised yearly. Many countries have adopted the principles of the United Nations convention on the rights of persons with disabilities as well as the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health to protect the rights and the quality of life (QoL) of those with disabilities to work and to do their choice of employment ( United Nations, 2006, 2011).

A study by the World Health Organization found that 15% of the global population (one in seven people) faces disability. The concept of disability is defined as “ the situation that allows contact between persons with impairments to deal with the environmental barriers that face their effective full contributions in the community compared with others in the same community” ( World Health Organization, 2023).

The number of enrolled students with disabilities in universities has increased yearly in many countries. The most common types of people with disabilities are classified as physical (37%), vision (36%), hearing and communication (21%), mental (4%), and others (1%) ( Milaat et al., 2001).

Disability is considered a significant social and economic problem facing many countries. People with disabilities have faced different challenges especially during and after graduating from their studies. Countries like Saudi Arabia have adopted a new initiative in education like the Saudi “School for All” initiative. This initiative represents a critical factor in improving the learning opportunities of disabled students in the Saudi public education system ( Bagadood and Sulaimani, 2023).

The Ministry of Higher Education in Saudi Arabia provides students with disabilities a chance to continue their higher education studies ( MOE, 2023). This effort helps to tackle the challenge of disability in the Saudi Arabian community. In addition, the Ministry of Human Resources sets different projects and initiatives to overcome the challenges that students with disabilities face during their working life ( HRSD, 2023).

This study aims to highlight the main factors that influence the quality of academic life of students with disabilities in universities. The study highlights the main opportunities and challenges that students with disabilities face during their university life. Very few studies have been conducted in Saudi Arabia to address this important issue.

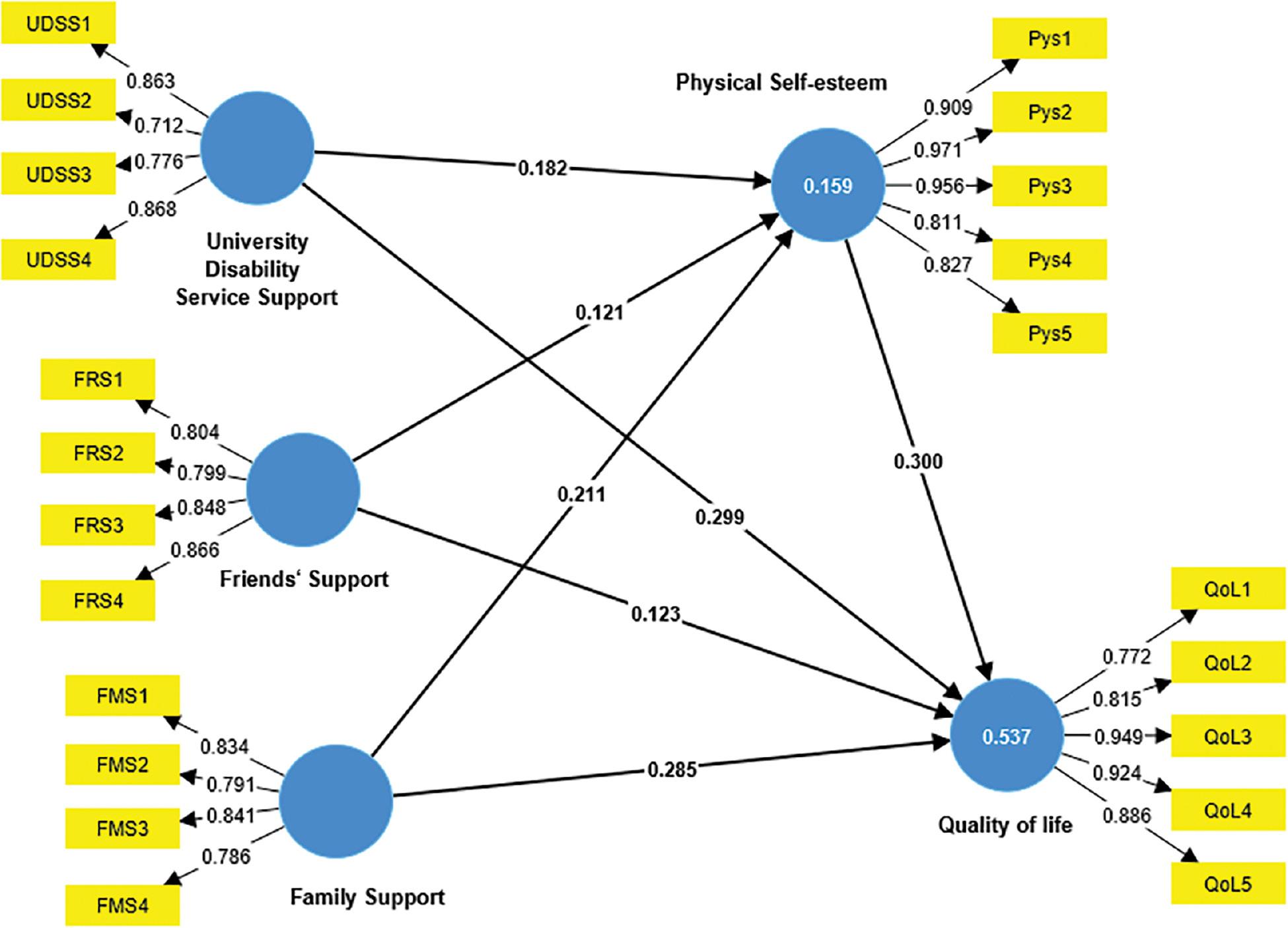

The QoL of disabled students at universities—the dependent variable—might be affected by different factors—independent variables—of this study. These variables include academic services, university support, family support, physical self-esteem, and friends’ support. This study is important and fills the gap in the literature of disability studies. We try to understand the mediation effects of the main variables. Thus, we have developed our model to understand how the QoL of students with disabilities is affected by these variables and how physical self-esteem mediates this relationship. In addition, we plan to provide Saudi universities with practical and academic recommendations to enhance the QoL of students with disabilities.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Disability services, physical self-esteem, and QoL of disabled students

University disability services play a crucial role in students’ academic performance, satisfaction, self-esteem, and QoL. Self-esteem is defined as how students feel better about themselves ( Canfield, 1990). Students with high levels of self-esteem will feel self-confident and see themselves as being responsible for their lives ( Holly, 1987). The university’s services, support, and facilities include two types. The first type focuses on students’ personal, social, and emotional needs. The second type focuses on their academic needs ( Prebble et al., 2004). Both types affect the quality of academic life for students especially those with disabilities. QoL is defined as an individual’s attitude and perception of their position in life regarding the culture and value systems in which they are supposed to live and their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns. The QoL level affects a person’s physical health, mental state, and level of independence. ( Majumdar and Jain, 2020; Cai et al., 2021).

Today, many universities provide students with disabilities with different types of services to improve their well-being. There are many examples of services and supports provided by universities for all students, especially disabled students. These include counseling services which have positively affected the retention rate, satisfaction, and self-esteem. These are very important academic indicators that reflect the quality of academic life for students ( Andrew and Berry, 2000). Researchers have classified the university services in a comprehensive list that includes child care, support services, financial aid, counseling services, health services, library support services, student housing services, employment services, and cafeteria/catering service ( McInnis et al., 2000).

Today, many universities have developed a diverse learning environment where diverse students with different characteristics can be enrolled, studied, and developed. These groups of diverse students might include disabled students ( Wolbring and Lillywhite, 2021). The adoption of inclusive and diverse education for disabled students requires major changes and modifications to existing education laws and the required services to ensure adequate students’ motivation, satisfaction, and success. However, in many countries, further steps are needed. The current laws in education may promote the idea of special education in different settings and encourage a shared understanding of inclusive education and its implementation ( United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2020).

Regarding sustainable disability services, the required services that meet the needs of disabled students constitute a major challenge and difficulty for new applicants with disabilities during their education journey ( Madhesh, 2023). These challenges might affect the QoL for disabled students.

Disabled students face different barriers and challenges during their learning experience including the physical environment, campus layout, room design, accommodation availability, library resources, and other support services ( Holloway, 2001; Redpath et al., 2013). Studies revealed that university services and social support are associated with high motivation and self-esteem ( Bum and Jeon, 2016).

There are different types of support offered to students with disabilities in universities through the Disabilities Service Units ( Couzens et al., 2015). These services and special supports are designed to enhance the knowledge, skills, capabilities, and self-esteem of students with disabilities ( Holmstrom, 2012). Different studies revealed that self-esteem is important and plays a crucial role in the success of students. It helps students to adapt their learning behaviors ( Supervía et al., 2023). If disabled students feel that they are treated fairly and equally in receiving the university’s support, this helps to improve their satisfaction, attitude, and success, which promotes students’ resiliency and mental health ( LaBelle, 2023; Tatsi and Panagiotopoulou, 2023). Thus, these services improve the perceptions of the quality of academic life which in turn is translated into high satisfaction and success.

Students with disabilities need special services support during their studies. These supports include different approaches like blended learning which helps students to improve their sustainable satisfaction, motivation, self-awareness, performance, and self-esteem ( Momchilova, 2021). Studies revealed that sustainable teachers for disabled students also improve their motivation, QoL, and self-esteem ( Ofiesh and Mather, 2023).

We argue that university support is necessary for all students, but the current support and services that are provided to meet the needs of disabled students are not enough. In addition, these services and supports should be measured and assessed to develop the university’s target outcomes. Studies revealed that when students can access and receive university services during their studies, this is negatively associated with stress in the university and leads to higher academic achievement that translates into high QoL. This also improves the self-esteem and students’ QoL ( Hamdan-Mansour and Dawani, 2008; Kim and Lee, 2016). Students’ support units such as coaching, advising, and orientation help students with disabilities to improve their self-awareness, self-esteem, academic life, self-management skills, and subjective well-being ( Rowe et al., 2020).

Friends support, physical self-esteem, and QoL for disabled students

Good friendships are critical for human and social life. Sustainable support from friends is very critical to disabled students. This type of support improves the level of satisfaction and provides motivation for disabled students ( Dreyer et al., 2020). Previous studies revealed that people with at least one reciprocal friend had higher self-esteem scores than those without a reciprocal friend ( Bishop and Inderbitzen, 1995; Keefe and Berndt, 1996). We can argue that positive self-esteem improves the ability of students with disabilities to create and maintain good friends. Therefore, the university must provide training and workshops on how to build and sustain good friendships.

If disabled students feel cared for as well as have full access to their friend’s support and sustainable relationships, this can impact their self-esteem, self-efficacy, and their emotional behavior. It also leads to improving the quality of their life and learning performance ( Crockett et al., 2007; Chao, 2011). A study revealed that good friendships at university improve students’ well-being, self-efficacy, and retention rate, and reduce stress ( Picton et al., 2017).

We can define good friendship at the university as a friendship that supports the learning outcomes. Students can mutually benefit from this type of friendly environment. The role of the university is to create and sustain a friendly learning environment to help disabled students motivate, satisfy, learn, and develop. Many students rely on the university’s friendships to help them do better in their coursework. This shows a good quality learning environment ( McCabe, 2019). This also affects the quality of their academic life which translates into high grades, positive emotional feelings, and high self-esteem. In addition, studies revealed that disabled students depend heavily on their friends as colleagues as a source of sustainable esteem support ( Bronkema and Bowman, 2019; Ahmed et al., 2023).

The good quality of academic life depends on many factors including the social and friendly environment at university ( Moriña and Biagiotti, 2022; Saeed et al., 2023). A study revealed that students with disabilities are less likely to receive friendship ties than their peers. Therefore, the role of the university is to create a social network environment designed to equip students with disabilities with sustainable social links to help them learn better and enjoy a high-quality life ( Mamas et al., 2020). This is driven mainly by the idea of the Social Networks Theory. This theory consists of people connected by relationships with one another and resources and information flow between them ( Borgatti and Ofem, 2010). Studies found that students’ QoL improves when students create a balance between their bodies, minds, and spirits and can establish and maintain a harmonious set of friendships ( Albrecht and Devlieger, 1999).

We argue that the university environment can play a proactive role in developing and maintaining healthy relationships among students. Friends’ support can help students with disabilities to retain, perform, and succeed during their academic life. If students with disabilities perceive their friendship and peer support positively, this leads to enhanced mental health, physical health, self-esteem, and QoL. When students with disabilities feel the care of their friends, this helps to improve their self-esteem, self-efficacy, emotional satisfaction, behavioral attitudes, and health outcomes ( Bender and Lösel, 1997). Many studies revealed that good relationships with peers and friends help students with disabilities to engage in their campus activities, succeed, and enjoy their social activities ( Lombardi et al., 2016).

Family support, physical self-esteem, and QoL for disabled students

Support from family is very critical for starting the university journey as well as the success of students with disabilities ( Dreyer et al., 2020; Moriña and Biagiotti, 2022). The parents of disabled students are the key factors that provide educational sessions, discussion groups, and career counseling. The family usually offers varied forms of social and cultural support that enable students with disabilities to positively influence their university life and improve their well-being, motivation, self-esteem, and academic success ( Duma and Shawa, 2019). Family advice and support are crucial to influencing disabled students’ motivation, self-efficacy, and self-esteem to continue and complete their studies. Family support helps students with disabilities to feel better about themselves ( da Silva Cardoso et al., 2016; Duma and Shawa, 2019).

Family environment affects the future of students with disabilities. A conducive family environment encourages disabled students to learn better. We argue that universities should build strong relationships with the families of students with disabilities. This leads to enhancing their roles which can be described as lower than expected. Studies revealed that students with disabilities show lower levels of satisfaction with support from both family and friends compared with their peers ( Dong and Lucas, 2014). Thus, the role of the family needs to be improved and evaluated regularly.

The QoL of students with disabilities is also influenced positively by their family’s support. The study revealed that family support helps students to improve their future and the quality of their lives. Family can play a critical role in encouraging students with disabilities to start their employment as well as entrepreneurship projects. This helps to improve their QoL ( Sultan et al., 2016). The study suggests that people need social and family support to improve their physiological conditions, reduce pain, and improve their QoL ( Sultan et al., 2016).

Family financial status and income support are also considered important for students with disabilities. The study found that students with disabilities who come from low-income families faced high stress and dissatisfaction compared with those who come from high-income families. This situation affects the QoL and the decision to discontinue the university journey ( Rojewski et al., 2015).

The lack of adequate family support can negatively affect the self-esteem and QoL of students with disabilities. Different studies revealed that adequate support from family members is associated with higher self-esteem ( Van Aken and Asendorpf, 1997).

The meditating effect of physical self-esteem

Different studies revealed that students’ self-esteem mediated the existing relationship between current social support and students’ QoL satisfaction. This means students with high self-esteem tend to show a high level of life satisfaction ( Kong and You, 2013).

The QoL of disabled students is affected by the level of their self-esteem. The universities, families, peers, and friends can shape the QoL when they control their self-esteem levels. This might be achieved through different services, strategies, and practices like academic support, social support, family support, and friends’ support. The study revealed that self-esteem significantly mediated the relationship between students’ services, resilience, support, and their QoL as well as their life satisfaction. Thus, it is very important to improve the level of self-esteem of students with disabilities to enhance their QoL ( Cheng et al., 2022).

We can argue that family is expected to play an important part compared with the university especially when it comes to improving the level of self-esteem of their disabled members. Sustainable social supports, services, and advice help students with disabilities to live with a high level of satisfaction, a positive perception of their life, high confidence, and thus improving their QoL in the future. Disabled students’ perceptions and assessments of their physical attributes, skills, and general physical value are referred to as physical self-esteem. Physical self-esteem can be extremely important in affecting a challenged student’s overall QoL. Disability services are tools that educational institutions and other organizations offer to help disabled students in both their academic and personal lives. In addition to accommodations, these services could also include therapeutic assistance, accessible facilities, assistive technology, and more. Disability services are designed to help impaired students thrive academically and improve their well-being by fostering an inclusive and encouraging atmosphere. By taking into account the mediating function of physical self-esteem, the relationship between disability services and the QoL of impaired students can be better understood. Understanding how disability services affect several areas of the student’s lives, such as psychological, social, and academic functioning, and physical self-esteem serves as a mediator in this interaction. For instance, accessibility to suitable accommodations and assistive technology through disability services can have a favorable impact on the physical capacities and functioning of impaired students. As a result, individuals may feel more confident about their physical capabilities and independence. Their QoL can be significantly impacted by improved physical self-esteem since it can result in greater self-confidence, self-acceptance, and general well-being. Furthermore, by addressing the psychosocial difficulties that impaired students may experience, disability services can also have a positive indirect effect on physical self-esteem. These difficulties may include social stigmatization, prejudice, or a lack of opportunity to participate in physical activity.

H7: Physical Self-esteem has a positive impact on the QoL of disabled students.

H8: Physical Self-esteem mediates the relationship between disability services and the QoL of disabled students.

In addition, physical self-esteem can act as a mediating factor in the relationship between friends’ support and the QoL of disabled students. The confidence and self-perception of impaired students might be boosted when they receive good feedback about their physical ability from their friends. They might grow to have a higher level of physical self-esteem as a result. The QoL of students with disabilities may improve as a result of greater physical self-esteem. It can enhance their general well-being, make them feel more at ease and secure in their bodies, and make it easier for them to engage in social, educational, and recreational activities. Additionally, improved mental health and psychological well-being can be facilitated by having a positive view of one’s physical appearance. In conclusion, physical self-esteem may mediate the relationship between friends.

Besides, the physical self-esteem of students with disabilities can be considerably impacted by the support they receive from their family members, which in turn can have an impact on their general well-being and level of happiness in life. Their physical self-esteem is positively impacted when impaired students receive support from their family members, including encouragement, understanding, and assistance in conquering physical problems. This assistance can take many different forms, including going with them to their doctor’s appointments, helping them with everyday tasks, offering emotional support, and speaking up for their needs. Students with disabilities may have a more favorable opinion of their physical capabilities and appearance if they feel their families are supporting them. They might feel more self-acceptance, confidence, and a sense of belonging. This can then result in an overall improvement in QoL and well-being. Disability-related factors are also influenced by one’s physical self-esteem. Thus, physical self-esteem may mediate the relationship between family support and the QoL for students with disabilities.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Operationalization of the study concepts

The study employed a variety of indicators derived from prior research, following a comprehensive review of the relevant literature. For instance, some researchers ( Zimet et al., 1988) have introduced the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) to gauge assistance from different sources. In this investigation, MSPSS was employed to assess both family support, encompassing four items (e.g. “I feel comfortable discussing my concerns with my family”), and friend support, involving four items (e.g. “I have confidence in my friends when confronted with challenges”). Similarly, the evaluation of University Disability Services Support (UDSS) entailed four items adapted from previous studies ( Lombardi et al., 2011) (e.g. “The Disability Services office effectively addresses specific incidents of insensitivity”). Moreover, the assessment of Physical Self-Esteem (PYS) drew upon a set of five items extracted from the physical self-concept section of the Physical Self-Description Questionnaire ( Marsh et al., 1994; Goñi Grandmontagne et al., 2004). This measurement tool offers a comprehensive appraisal of an individual’s positive sentiments regarding their physical self ( Marsh et al., 1994; Pavot and Diener, 2008). Respondents were prompted to react to five queries (e.g. “I am satisfied with my physical appearance and abilities”).

Lastly, the “Satisfaction with Life Scale” (SWLS), developed by Diener et al. (1985), was incorporated in our study, consisting of five items to gauge QoL. The SWLS assesses an individual’s overall cognitive evaluation of their contentment with life. Participants were asked to express their level of agreement with statements relating to their happiness. Examples of these statements are: “My life circumstances are excellent” and “I wouldn’t change much if I could relive my life”. Each statement was rated on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Participants and process of data collection

The study follows a deductive and quantitative approach. It involves the collection of a sample from disabled students enrolled in various university programs, including Finance, Computer Science, Human Resource Management, Accounting, Computer Science, Arts, and Medicine, across four prominent universities in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: King Faisal University, Al-Hofuf (Eastern Province); Imam Mohammad ibn Saud Islamic University, Riyadh (Riyadh Province); Umm Al-Qura University, Mecca (Mecca Province); and King Khalid University, Abha (Asir Province). These universities were chosen due to their prominent standing in Saudi Arabia, making them representative of the larger context.

The data collection process was thoughtfully designed to accurately represent the viewpoints of disabled students while upholding their rights and privacy. The research design was carefully crafted to encompass a diverse spectrum of disabilities, acknowledging the distinct challenges and requirements associated with varying conditions. The selection of participants occurred through diverse avenues, including disability services offices and academic departments. A concerted effort was made to ensure the inclusion of participants representing a variety of disability types. Throughout the data collection process, ethical considerations remained of utmost importance. Researchers strictly adhered to guidelines stipulated by relevant institutional review boards to ensure that participants were not exposed to any harm or undue stress. To validate the effectiveness of the data collection methods and the accessibility measures, a pilot testing phase was conducted involving a small group of disabled students (20 students). The feedback gathered during this phase was meticulously integrated to enhance the clarity and efficacy of the questionnaire.

The study utilized a random sampling method to select its sample of students, a process carried out during the months of April and May, 2023. The research collected data from a total of 400 respondents who were enrolled in the aforementioned programs. To gather this data, an online survey was administered via e-mail to the participants over the course of April to May 2023. Recognizing that the primary respondents of the study were non-English speakers, the original questionnaire and measurement tools were translated into Arabic to ensure ease of comprehension and engagement for the participants. To ensure the questionnaire’s quality, a pilot study involving a sample of 15 participants was conducted. This pilot study yielded no issues, leading to the distribution of the questionnaire link to the intended respondents. Following the removal of forms that did not meet the qualification criteria, a total of 368 valid responses were considered, resulting in a commendable recovery rate of 92%. The composition of the study sample encompassed 268 males (67%) and 100 females (33%). Notably, the age distribution of the participants primarily fell within the range of 18 to 25 years.

Data analysis methods

For the purpose of data analysis and hypothesis testing, the study employed partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Recognized as a straightforward yet powerful approach, PLS-SEM is employed to unravel intricate interactions among numerous constructs, allowing for the estimation and prediction of models. This method is particularly favored due to its suitability for small sample sizes and a host of other advantages ( Hair et al., 2019). Effective application of PLS-SEM involves the completion of two fundamental steps: the formulation of both the structural (inner) and measurement (outer) models ( Hair et al., 2011). In evaluating the outer measurement model, the study adhered to the criteria endorsed by Hair et al. (2017). These criteria encompass diverse threshold metrics such as “standardized factor loading” (>0.7), “composite reliability (CR)” (>0.7), “average variance extracted (AVE)” (>0.5), R2 (>0.1), and Stone-Geisser Q2 (>0.0).

THE STUDY RESULTS

Outer model assessment

In the analysis of PLS-SEM modeling, the initial step involves the assessment of the measurement model. Within this evaluation, various tests are employed to scrutinize factors such as indicator and construct loadings, reliability, and validity. Fundamental assessments conducted within the measurement model encompass Cronbach’s alpha (CA), CR, AVE, and variance inflation factor (VIF). When scrutinizing indicator loadings, it is advised that these values ideally exceed 0.70. This threshold signifies the indicator’s ability to account for approximately 50% of variance, indicating enhanced reliability ( Sarstedt et al., 2021). While the recommendation of 0.70 as a loading threshold holds significance, it’s noteworthy that values <0.70 should not be excluded unless their removal unequivocally guarantees an increase in CR. The outcomes depicted in Table 1 reveal positive indicators loading reliability. For the study’s constructs to maintain internal consistency and reliability, CR and CA values should ideally fall between 0.70 and 0.95 to ensure enhanced reliability and validity ( Hair et al., 2017). The findings displayed in Table 1 affirm the accomplishment of the desired threshold.

Psychometric attributes.

| Outer loadings | Cronbach’s alpha | CR (rho_a) | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cut-off point | >0.7 | >0.7 | >0.7 | >0.5 |

| University disability service support | 0.825 | 0.864 | 0.652 | |

| UDSS1 | 0.863 | |||

| UDSS2 | 0.712 | |||

| UDSS3 | 0.776 | |||

| UDSS4 | 0.868 | |||

| Friends support | 0.849 | 0.854 | 0.688 | |

| FRS1 | 0.804 | |||

| FRS2 | 0.799 | |||

| FRS3 | 0.848 | |||

| FRS4 | 0.866 | |||

| Family support | 0.831 | 0.845 | 0.661 | |

| FMS1 | 0.834 | |||

| FMS2 | 0.791 | |||

| FMS3 | 0.841 | |||

| FMS4 | 0.786 | |||

| Physical self-esteem | 0.938 | 0.946 | 0.805 | |

| PYS1 | 0.909 | |||

| PYS2 | 0.971 | |||

| PYS3 | 0.956 | |||

| PYS4 | 0.811 | |||

| PYS5 | 0.827 | |||

| Quality of life | 0.919 | 0.925 | 0.760 | |

| QoL1 | 0.772 | |||

| QoL2 | 0.815 | |||

| QoL3 | 0.949 | |||

| QoL4 | 0.924 | |||

| QoL5 | 0.886 |

Abbreviations: AVE, average variance extracted; CR, composite reliability; FMS, Family Marital Support; UDSS, University Disability Services Support.

Moreover, the examination of the AVE test is warranted, as it serves to evaluate the convergent validity within the study. A recommended threshold of 0.50 or higher for AVE is suggested by Sarstedt et al. (2021). The AVE values presented in Table 1 indicate their acceptability and alignment with the prescribed threshold. Subsequently, the assessment of multicollinearity is conducted through the VIF test, which illuminates the strength of correlations among exogenous variables within the study. A value <5 for AVE indicates the absence of collinearity within the study ( Hair et al., 2019).

The evaluation of variable uniqueness holds significant importance within this context. Hence, for the sake of achieving discriminant validity, the outer factor loading of the reflective items should surpass the cross-loading values associated with the relevant scale measures (refer to Table 2). Additionally, we conducted the test proposed by researchers ( Fornell and Larcker, 1981). The findings, as presented in Table 3, underscore the presence of satisfactory discriminant validity. Furthermore, an exploration of the extent to which a construct maintains empirical distinctiveness from other constructs in the structural model was carried out using the Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio test—a more precise assessment ( Hair et al., 2019). Our findings, as demonstrated in Table 4, exhibited acceptable outcomes, with no values exceeding 0.90. This indicates the absence of discriminatory issues among the research constructs.

Cross-loadings.

| FMS | FRS | PYS | QoL | UDSS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FMS1 | 0.834 | 0.397 | 0.305 | 0.573 | 0.428 |

| FMS2 | 0.791 | 0.223 | 0.187 | 0.359 | 0.290 |

| FMS3 | 0.841 | 0.306 | 0.329 | 0.475 | 0.426 |

| FMS4 | 0.786 | 0.324 | 0.289 | 0.465 | 0.455 |

| FRS1 | 0.409 | 0.804 | 0.130 | 0.338 | 0.155 |

| FRS2 | 0.209 | 0.799 | 0.147 | 0.287 | 0.104 |

| FRS3 | 0.390 | 0.848 | 0.219 | 0.312 | 0.217 |

| FRS4 | 0.293 | 0.866 | 0.285 | 0.282 | 0.168 |

| PYS1 | 0.285 | 0.201 | 0.909 | 0.466 | 0.286 |

| PYS2 | 0.366 | 0.251 | 0.971 | 0.539 | 0.324 |

| PYS3 | 0.314 | 0.217 | 0.956 | 0.463 | 0.266 |

| PYS4 | 0.301 | 0.201 | 0.811 | 0.456 | 0.271 |

| PYS5 | 0.295 | 0.200 | 0.827 | 0.405 | 0.242 |

| QoL1 | 0.431 | 0.267 | 0.420 | 0.772 | 0.460 |

| QoL2 | 0.478 | 0.435 | 0.535 | 0.815 | 0.465 |

| QoL3 | 0.579 | 0.328 | 0.503 | 0.949 | 0.539 |

| QoL4 | 0.552 | 0.290 | 0.438 | 0.924 | 0.504 |

| QoL5 | 0.513 | 0.264 | 0.362 | 0.886 | 0.463 |

| UDSS1 | 0.513 | 0.172 | 0.224 | 0.441 | 0.863 |

| UDSS2 | 0.338 | 0.283 | 0.164 | 0.473 | 0.712 |

| UDSS3 | 0.316 | 0.080 | 0.099 | 0.275 | 0.776 |

| UDSS4 | 0.420 | 0.094 | 0.409 | 0.531 | 0.868 |

Abbreviations: FMS, Family Marital Support; UDSS, University Disability Services Support.

Fornell–Larcker criterion matrix.

| FMS | FRS | PYS | QoL | UDSS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family support | 0.813 | ||||

| Friends’ support | 0.395 | 0.830 | |||

| Physical self-esteem | 0.350 | 0.240 | 0.897 | ||

| Quality of life | 0.589 | 0.367 | 0.522 | 0.872 | |

| University disability service support | 0.501 | 0.197 | 0.312 | 0.560 | 0.807 |

Abbreviations: FMS, Family Marital Support; UDSS, University Disability Services Support.

Inner model assessment

Upon completion of the measurement model, the structural model underwent testing. The outcomes of the correlations, hypothesis evaluations, and other pertinent tests are displayed in Table 5. This table provides insight into the findings of the tested hypotheses within the study. Initiating with Hypothesis 1 (H1), a noteworthy positive and significant association between UDSS and physical self-esteem (PYS) was identified among the study’s respondents (β = 0.182, P < 0.001). The Table further divulges the corresponding effect size (F2), which stands at 0.030, signifying a modest effect size according to Cohen’s criteria (1988). Furthermore, the t-value for the UDSS and PYS relationship underscores that 3.697 of the variances in PYS can be expounded by UDSS. Moving ahead, Table 5 unveils the findings of Hypothesis 2 (H2), revealing a positive and statistically significant connection between UDSS and QoL among the participants (β = 0.299, P < 0.001). The associated effect size (F2) for this relationship is determined as 0.141, consistent with a small effect as classified by Cohen (1988). The t-value for the relationship between UDSS and QoL indicates that 6.414 of the variances in QoL can be accounted for by UDSS.

Results of inner model.

| Hypotheses | β | STDEV | T-value | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| University disability service support -> physical self-esteem (H1) | 0.182 | 0.049 | 3.697*** | Confirmed |

| University disability service support -> Quality of life (H2) | 0.299 | 0.047 | 6.414*** | Confirmed |

| Friends‘ support -> physical self-esteem (H3) | 0.121 | 0.053 | 2.280* | Confirmed |

| Friends‘ support -> quality of life (H4) | 0.123 | 0.034 | 3.612*** | |

| Family support -> physical self-esteem (H5) | 0.211 | 0.051 | 4.128*** | Confirmed |

| Family support -> quality of life (H6) | 0.285 | 0.046 | 6.143*** | Confirmed |

| Physical self-esteem -> quality of life (H7) | 0.300 | 0.032 | 9.506*** | Confirmed |

| University disability service support -> physical self-esteem -> quality of life (H8) | 0.063 | 0.017 | 3.740*** | Confirmed |

| Friends support -> physical self-esteem -> quality of life (H9) | 0.036 | 0.016 | 2.256* | Confirmed |

| Family support -> physical self-esteem -> quality of life (H10) | 0.055 | 0.017 | 3.128** | Confirmed |

Abbreviation: STDEV, Standard Deviation.

Furthermore, the study’s outcomes in relation to Hypothesis 3 (H3) exhibit a positive and significant link between Family Relationship Support (FMS) and physical self-esteem (PYS) among the respondents (β = 0.121, P < 0.05). The corresponding effect size (F2) for this connection is calculated at 0.015, aligning with a small effect size as per Cohen (1988). The t-value for the FRS and PYS relationship indicates that 2.280 of the variances in PYS are influenced by FRS. Turning to Hypothesis 4 (H4), which explores the relationship between FRS and QoL, the study’s findings unveil a positive and statistically significant connection between the two (β = 0.123, P > 0.001). The effect size (F2) associated with the FRS and QoL relationship is computed as 0.027, corroborating the presence of a small effect, as denoted by Cohen’s criteria ( Cohen, 1988). The t-value for the FRS and QoL relationship registers a value of 3.612, lending support to Hypothesis 4 (see Fig. 1).

As for Hypothesis 5 (H5), its aim was to explore the association between Family Marital Support (FMS) and physical self-esteem (PYS). The results revealed a positive and statistically significant relationship (β = 0.211, P < 0.001). Furthermore, the effect size (F2) of 0.035, in alignment with Cohen’s criteria (1988), signifies the presence of a small effect. The t-value corresponding to the FMS and PYS relationship indicates that 4.128 of the variances in PYS can be elucidated by FMS. Shifting the focus to Hypothesis 6 (H6), the study’s findings unveiled a positive and significant connection between FMS and QoL (β = 0.285, P < 0.001). The associated effect size (F2) is calculated as 0.112, reaffirming a small effect size as outlined by Cohen (1988). Moreover, the t-value associated with the FMS and QoL relationship points out that 6.143 of the variances in QoL can be comprehended through FMS. Furthermore, Hypothesis 7 (H7) investigated the link between physical self-esteem (PYS) and QoL. The findings highlighted a positive and significant association (β = 0.30, P < 0.001) with a mediating effect size (F2) of 0.163, in accordance with Cohen’s criteria ( Cohen, 1988). The t-value, standing at 9.506, provides further support for Hypothesis 7 by indicating that 9.506 of the variances in QoL can be attributed to PYS.

Regarding Hypothesis 8 (H8), which aimed to assess whether physical self-esteem (PYS) could mediate the connection between UDSS and QoL, the findings indicated a mediating role of PYS in the aforementioned paths (β = 0.063, P > 0.001), supported by a t-value of 3.740. Furthermore, Hypothesis 9 (H9) delved into the potential mediating role of PYS between Family Relationship Support (FMS) and QoL, yielding intriguing results. The outcomes of H9 demonstrated the mediating ability of PYS in the relationship between FRS and QoL (β = 0.036, P < 0.05), validated by a t-value of 2.256. Finally, Hypothesis 10 (H10) explored whether FMS and QoL could be mediated by PYS. The results underscored PYS’s capacity to mediate the link between FMS and QoL (β = 0.055, P < 0.01), with a t-value of 3.128 in support of H10. Addressing the coefficient of determination (R2), which quantifies the proportion of variances predictable by the studied factors, it is evident that UDSS, FRS, and FMS together could predict 0.159 of the variances in PYS. Additionally, when considering UDSS, FRS, FMS, and PYS combined, they accounted for 0.537 of the variances in QoL, representing a substantial predictive capacity. Lastly, the study assessed the predictive relevance of its model using Q2, revealing that all Q2 values surpass 0. This suggests that the study’s model possesses significant predictive relevance ( Hair et al., 2019).

Furthermore, an examination of Common Method Bias (CMB) through Harman’s single-factor test was conducted. The resulting CMB value stood at 41%, falling below the threshold of 50%. This observation signifies the absence of any significant CMB in the study ( Podsakoff et al., 2003).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

This study intends to identify the key elements that affect the academic life quality of university students with disabilities. The study identifies the key possibilities and difficulties that students with impairments encounter while attending college. Five aspects of the relationships are examined in this study: (1) the direct relationship between university support (UDSS), friends’ support (FRS), FMS, physical self-esteem (PYS), and QoL; (2) the direct effects of PYS on QoL; and (3) the mediating role of PYS in the relationship between UDSS, FRS, and FMS on QoL. The results of this study came to support earlier research findings, which found beneficial connections between physical self-esteem and university services support ( Bum and Jeon, 2016). The physical self-esteem of students with disabilities would therefore improve when colleges pay attention to the assistance for disability services. As a result of this finding, we advise Saudi universities to establish specialized disability service support units to effectively administer disability services.

The association between healthy young adults and university students’ levels of physical exercise and the results of such activity (particularly, their learning experience, QoL, and levels of physical self-esteem) has only been briefly examined in published studies. As a result, less is known about the mental (QoL and learning environment) and physical (physical self-esteem) consequences related to different PYS levels among young people and university students. The transition from high school to college presents specific problems for disabled university students, hence they are of particular importance. Students with disabilities who attend universities frequently face additional accountability, competition, academic pressure, and time management demands. Reduced physical self-esteem activity (PYS), as well as increased emotional and psychological stress issues, may follow this alteration. Consequently, we recommend that the Saudi Ministry of Education revise its current university statute to offer enough motivation and pleasure for impaired students. As a result, more research is needed to establish what buffering elements, if any, may help university students enhance their QoL and physical self-esteem in the long term. The current study looks into the effect of UDSS on QoL via the mediating role of PYS.

This study’s findings supported the good direct influence of FRS on QoL and PYS. These findings are consistent with earlier studies indicating the value of friends’ support in boosting the level of happiness and motivation among impaired students ( Bishop and Inderbitzen, 1995). Furthermore, maintaining positive interactions with friends and peers will have a significant impact on their self-esteem and self-efficacy ( Keefe and Berndt, 1996). As a result, higher commitment to FRS is connected with increased and better QoL as well as learning performance ( Sigstad, 2016). This makes sense, given that research indicates that impaired students who participate in strong friend relationships have higher self-esteem and positive moods than those who do not ( Grunebaum and Solomon, 1987). The benefits of FRS can be divided into four categories: an increase in self-esteem, improved mental health, a learning experience, and a significant improvement in one’s QoL. Saudi institutions must devise a strategy to maintain friendships between impaired students and other students based on their genuine requirements by holding workshops. Also, unique events can be organized outside of the university campus that incorporate local communities in order to strengthen the networks of disabled students.

The findings of this study indicated that a direct influence of FMS on QoL and PYS. These findings confirm prior research that emphasizes the importance of the family in assisting disabled students in enhancing their motivation, well-being, self-esteem, and academic performance ( Brillhart, 1988). Furthermore, the study findings revealed that FMS has a considerable impact on QoL and PYS. This result is consistent with previous studies ( Duma and Shawa, 2019).

The current study’s findings imply that FMS is critical for improving student QoL. FMS can improve QoL, with a single moderate FMS exercise having a significant impact on students’ capacity to comprehend theoretical concepts and establish a better learning environment, with participants with a high level of physical self-esteem greatly increasing. It was determined that FMS significantly improved FYS. This finding is consistent with earlier studies showing a link between high FMS levels and academic success ( Sultan et al., 2016). These results show how crucial FMS is to ensuring that students make progress in their studies. Despite a substantial correlation between FMS and student behavior and perceived academic competency, very little research has looked at the relationship between FMS and the actual learning process. The learning experience seems to benefit from high FMS levels, which enhances future QoL. Since they are generally content, students are more likely to do well in school and think favorably about their future careers and employment. We recommend that the university build a good relationship with disabled students’ families via disabled support units. In addition, families should be involved in developing strategies and decision-making related to disabled students at the university.

The findings of this study supported the positive direct impact of PYS on QoL. In addition, the study findings highlighted the significant impact of PYS on QoL. This result is in line with that of Aldaqal and Sehlo (2013). The findings of the present study suggest that PYS is essential to improve student QoL. PYS can promote learning experience (LE), with just a single exercise of moderate PYS having a significant impact on the learning environment and significantly improving participants with a high level of QoL. PYS was found to have a positive significant impact on the relation between FRS and QoL. This result represents a good contribution to this research in the current literature. This finding demonstrates the importance of PYS to have greater educational and recreational activities. Few studies have examined the relationship between FRS and QoL, despite the fact that there is a strong relationship between QoL and FRS and perceived academic competence. High levels of QoL appear to have a positive effect on improving impaired students’ mental health and psychological well-being.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Universities should devote greater resources and funds to disability services departments to guarantee that they have the staff, equipment, and programs needed to serve disabled students. In addition, thorough training should be provided to disability services employees in order to improve their ability to effectively understand, predict, and respond to the needs of students with disabilities. University should conduct frequent accessibility audits of university buildings, facilities, and online platforms in order to identify and eliminate any hurdles or difficulties that may prevent students with disabilities from participating. It is highly recommended to enhance communication by implementing clear and accessible communication channels to increase accessibility of disability services and encourage students to seek help. This could include developing an easy-to-use website, distributing materials in numerous forms, and employing clear language.

Universities should provide accessible digital resources, accommodations, assistive technologies, and sign language interpreters to assist impaired students. These services should be easily accessible and readily available. It is recommended to provide training programs or workshops to educate the university community on the many sorts of impairments, their effects, and how to provide inclusive support.

IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY

The study has some academic and managerial implications. Universities can attract a variety of students with disabilities by providing comprehensive disability services and accommodations. This can result in more enrollment, which means more tuition revenues for private universities and potential growth in associated programs and services. Effective disability services can also help students stay in university longer. When students with disabilities receive the academic support they require, they are more likely to persist and earn their degrees on time. Higher retention rates can help the university’s image and financial stability.

The study also has some social implication. Universities that prioritize disability services and are known for their inclusive atmosphere are more likely to attract students, faculty, and funding for government and other organizations. A positive reputation for assisting students with disabilities can have long-term economic benefits through increasing contributions, research grants, and other forms of funding.