- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Water, Sanitation, Hygiene, and Soil-Transmitted Helminth Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Read this article at

Abstract

Abstract

Background

Preventive chemotherapy represents a powerful but short-term control strategy for soil-transmitted helminthiasis. Since humans are often re-infected rapidly, long-term solutions require improvements in water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH). The purpose of this study was to quantitatively summarize the relationship between WASH access or practices and soil-transmitted helminth (STH) infection.

Methods and Findings

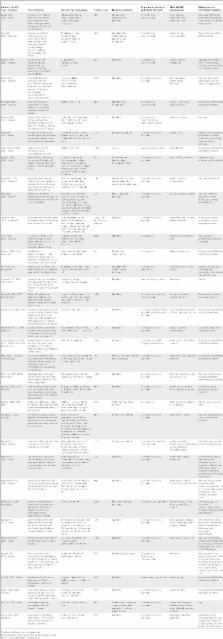

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to examine the associations of improved WASH on infection with STH ( Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, hookworm [ Ancylostoma duodenale and Necator americanus], and Strongyloides stercoralis). PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and LILACS were searched from inception to October 28, 2013 with no language restrictions. Studies were eligible for inclusion if they provided an estimate for the effect of WASH access or practices on STH infection. We assessed the quality of published studies with the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach. A total of 94 studies met our eligibility criteria; five were randomized controlled trials, whilst most others were cross-sectional studies. We used random-effects meta-analyses and analyzed only adjusted estimates to help account for heterogeneity and potential confounding respectively.

Use of treated water was associated with lower odds of STH infection (odds ratio [OR] 0.46, 95% CI 0.36–0.60). Piped water access was associated with lower odds of A. lumbricoides (OR 0.40, 95% CI 0.39–0.41) and T. trichiura infection (OR 0.57, 95% CI 0.45–0.72), but not any STH infection (OR 0.93, 95% CI 0.28–3.11). Access to sanitation was associated with decreased likelihood of infection with any STH (OR 0.66, 95% CI 0.57–0.76), T. trichiura (OR 0.61, 95% CI 0.50–0.74), and A. lumbricoides (OR 0.62, 95% CI 0.44–0.88), but not with hookworm infection (OR 0.80, 95% CI 0.61–1.06). Wearing shoes was associated with reduced odds of hookworm infection (OR 0.29, 95% CI 0.18–0.47) and infection with any STH (OR 0.30, 95% CI 0.11–0.83). Handwashing, both before eating (OR 0.38, 95% CI 0.26–0.55) and after defecating (OR 0.45, 95% CI 0.35–0.58), was associated with lower odds of A. lumbricoides infection. Soap use or availability was significantly associated with lower infection with any STH (OR 0.53, 95% CI 0.29–0.98), as was handwashing after defecation (OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.24–0.90).

Observational evidence constituted the majority of included literature, which limits any attempt to make causal inferences. Due to underlying heterogeneity across observational studies, the meta-analysis results reflect an average of many potentially distinct effects, not an average of one specific exposure-outcome relationship.

Conclusions

WASH access and practices are generally associated with reduced odds of STH infection. Pooled estimates from all meta-analyses, except for two, indicated at least a 33% reduction in odds of infection associated with individual WASH practices or access. Although most WASH interventions for STH have focused on sanitation, access to water and hygiene also appear to significantly reduce odds of infection. Overall quality of evidence was low due to the preponderance of observational studies, though recent randomized controlled trials have further underscored the benefit of handwashing interventions. Limited use of the Joint Monitoring Program's standardized water and sanitation definitions in the literature restricted efforts to generalize across studies. While further research is warranted to determine the magnitude of benefit from WASH interventions for STH control, these results call for multi-sectoral, integrated intervention packages that are tailored to social-ecological contexts.

Please see later in the article for the Editors' Summary

Editors' Summary

Background

Worldwide, more than a billion people are infected with soil-transmitted helminths (STHs), parasitic worms that live in the human intestine (gut). These intestinal worms, including roundworm, hookworm, and whipworm, mainly occur in tropical and subtropical regions and are most common in developing countries, where personal hygiene is poor, there is insufficient access to clean water, and sanitation (disposal of human feces and urine) is inadequate or absent. STHs colonize the human intestine and their eggs are shed in feces and enter the soil. Humans ingest the eggs, either by touching contaminated ground or eating unwashed fruit and vegetables grown in such soil. Hookworm may enter the body by burrowing through the skin, most commonly when bare-footed individuals walk on infected soil. Repeated infection with STHs leads to a heavy parasite infestation of the gut, causing chronic diarrhea, intestinal bleeding, and abdominal pain. In addition the parasites compete with their human host for nutrients, leading to malnutrition, anemia, and, in heavily infected children, stunting of physical growth and slowing of mental development.

Why Was This Study Done?

While STH infections can be treated in the short-term with deworming medication, rapid re-infection is common, therefore a more comprehensive program of improved water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) is needed. WASH strategies include improvements in water access (e.g., water quality, water quantity, and distance to water), sanitation access (e.g., access to improved latrines, latrine maintenance, and fecal sludge management), and hygiene practices (e.g., handwashing before eating and/or after defecation, water treatment, soap use, wearing shoes, and water storage practices). WASH strategies have been shown to be effective for reducing rates of diarrhea and other neglected tropical diseases, such as trachoma; however, there is limited evidence linking specific WASH access or practices to STH infection rates. In this systematic review and meta-analysis, the researchers investigate whether WASH access or practices lower the risk of STH infections. A systematic review uses predefined criteria to identify all the research on a given topic; a meta-analysis is a statistical method that combines the results of several studies.

What Did the Researchers Do and Find?

The researchers identified 94 studies that included measurements of the relationship between WASH access and practices with one or more types of STHs. Meta-analyses of the data from 35 of these studies indicated that overall people with access to WASH strategies or practices were about half as likely to be infected with any STH. Specifically, a lower odds of infection with any STH was observed for those people who use treated water (odd ratio [OR] of 0.46), have access to sanitation (OR of 0.66), wear shoes (OR of 0.30), and use soap or have soap availability (OR of 0.53) compared to those without access to these practices or strategies. In addition, infection with roundworm was less than half as likely in those who practiced handwashing both before eating and after defecating than those who did not practice handwashing (OR of 0.38 and 0.45, respectively).

What Do These Findings Mean?

The studies included in this systematic review and meta-analysis have several shortcomings. For example, most were cross-sectional surveys—studies that examined the effect of WASH strategies on STH infections in a population at a single time point. Given this study design, people with access to WASH strategies may have shared other characteristics that were actually responsible for the observed reductions in the risk of STH infections. Consequently, the overall quality of the included studies was low and there was some evidence for publication bias (studies showing a positive association are more likely to be published than those that do not). Nevertheless, these findings confirm that WASH access and practices provide an effective control measure for STH. Controlling STHs in developing countries would have a huge positive impact on the physical and mental health of the population, especially children, therefore there should be more emphasis on expanding access to WASH as part of development guidelines and targets, in addition to short-term preventative chemotherapy currently used.

Additional Information

Please access these websites via the online version of this summary at http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001620.

-

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also provides detailed information on roundworm, whipworm, and hookworm infections

-

The World Health Organization provides information on soil-transmitted helminths, including a description of the current control strategy

-

Children Without Worms (CWW) partners with Johnson & Johnson, GlaxoSmithKline, the World Health Organization, national ministries of health and education, non-governmental organizations, and others to promote treatment and prevention of soil-transmitted helminthiasis. CWW advocates a four-pronged, comprehensive control strategy—Water, Sanitation, Hygiene Education, and Deworming (WASHED) to break the cycle of reinfection

-

The Global Network for Neglected Tropical Diseases, an advocacy initiative dedicated to raising the awareness, political will, and funding necessary to control and eliminate the most common neglected tropical diseases, provides information on infections with roundworm (ascariasis), whipworm (trichuriasis), and hookworm

-

WASH for the Neglected Tropical Diseases is a repository of information on WASH and the neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) such as soil-transmitted helminthiasis, and features a resource titled “WASH and the NTDs: A Manual for WASH Implementers.”

-

Two international programs promoting water sanitation are the World Health Organization Water Sanitation and Health program and the World Health Organization/United Nations Childrens Fund Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation

Related collections

Most cited references129

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Water, sanitation and hygiene for the prevention of diarrhoea

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

Schistosomiasis and neglected tropical diseases: towards integrated and sustainable control and a word of caution.

- Record: found

- Abstract: not found

- Article: not found