- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Burden of disease attributable to unsafe drinking water, sanitation, and hygiene in domestic settings: a global analysis for selected adverse health outcomes

Read this article at

Summary

Background

Assessments of disease burden are important to inform national, regional, and global strategies and to guide investment. We aimed to estimate the drinking water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH)-attributable burden of disease for diarrhoea, acute respiratory infections, undernutrition, and soil-transmitted helminthiasis, using the WASH service levels used to monitor the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as counterfactual minimum risk-exposure levels.

Methods

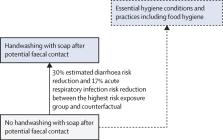

We assessed the WASH-attributable disease burden of the four health outcomes overall and disaggregated by region, age, and sex for the year 2019. We calculated WASH-attributable fractions of diarrhoea and acute respiratory infections by country using modelled WASH exposures and exposure–response relationships from two updated meta-analyses. We used the WHO and UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene public database to estimate population exposure to different WASH service levels. WASH-attributable undernutrition was estimated by combining the population attributable fractions (PAF) of diarrhoea caused by unsafe WASH and the PAF of undernutrition caused by diarrhoea. Soil-transmitted helminthiasis was fully attributed to unsafe WASH.

Findings

We estimate that 1·4 (95% CI 1·3–1·5) million deaths and 74 (68–80) million disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) could have been prevented by safe WASH in 2019 across the four designated outcomes, representing 2·5% of global deaths and 2·9% of global DALYs from all causes. The proportion of diarrhoea that is attributable to unsafe WASH is 0·69 (0·65–0·72), 0·14 (0·13–0·17) for acute respiratory infections, and 0·10 (0·09–0·10) for undernutrition, and we assume that the entire disease burden from soil-transmitted helminthiasis was attributable to unsafe WASH.

Related collections

Most cited references56

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010

- Record: found

- Abstract: not found

- Article: not found

GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations.

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found