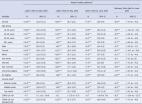

The Italian Ministry of Health, jointly with the Department of Infectious Diseases of the Italian National Institute of Health (Istituto Superiore di Sanità [ISS]), promptly built the integrated surveillance system for COVID‐19. To evaluate the severity of the virus spread, the reproduction number R t , defined as the average number of cases generated by an infected individual in a population where everyone is susceptible to infection, is estimated. Unfortunately, in Italy, R t is not only used to provide a picture of the epidemic spread but rather as a decision tool to plan and organize nonpharmaceutical interventions by imposing a priori thresholds to define different levels of risks, on which daily‐life restrictions apply. We believe this is a misuse of R t , which is dangerous and widely uncertain. For this reason, it is important that this parameter as an indicator for restriction measures must be managed by an expert in the field. Some practical and statistically relevant considerations are given in Gostic et al. 1 Nature (https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-02009-w), in July, already discussed the potential bias in using R t over its real meaning. Here, we discuss the main limits of the Italian approach to estimate and use R t , showing that the restrictions imposed on the population are based on an unreliable estimate of the reproduction number. The reference model is proposed by Cori et al. 2 The reproduction number is estimated in a Bayesian framework and requires the a priori definition/estimation of some fundamental quantities needed to estimate R t . The authors correctly discussed the limitations of their approach, but it seems that the Italian authorities neglect them. The main issues are related to the time window defined to estimate R t ; the distributions assumed to model the number of new cases and the generation time. The first risk is clearly stated in the Introduction, “When the data aggregation time step is small (e.g., daily data), estimates of R t can vary considerably over short time periods, producing substantial negative autocorrelation.” In other words, the obtained estimates of R t depend on the choice of the time window size. Which are the risks to consider an inappropriate time window? Small values lead to more rapid detection of changes in transmission but also more statistical noise; large values lead to more smoothing and reductions in statistical noise. Cori et al. 2 suggest an approach to detect the optimal time window based on the coefficient of variation. How this is dealt with in Italy is swept under the carpet. Moreover, Cori et al. 2 assumed that the distribution of infectiousness through time after infection is independent of calendar time and follows a Poisson process, that is, overdispersion is not accounted for. This is a rather restrictive assumption that must be carefully checked on the real data. It is well‐known that Poisson‐based estimates are biased if overdispersion arises in the data. We believe these points are already enough to conclude that the estimates of R t should be used with caution, but the most relevant assumptions strongly affecting the estimates of R t are not still discussed. Indeed, in Cori et al. 2 we further read, “Estimates of the reproduction number are highly dependent on the choice of the infectiousness profile. This can be approximated by the distribution of the generation time (i.e., time from the infection of a primary case to infection of the cases he/she generates). However, times of infection are rarely observed and the generation time distribution is therefore difficult to measure. On the other hand, the timing of symptoms onset is usually known and such data collected in closed settings where transmission can reliably be ascertained (e.g., households) can be used to estimate the distribution of the serial interval (time between symptoms onset of a case and symptoms onset of his/her secondary cases).” In other words, different estimates of the serial interval lead to different estimates of R t , that is, a reliable estimate of the serial interval is mandatory because it drives the estimate of R t , and its misspecification is the major source of bias. In Italy, the reference serial interval to estimate the official R t is taken from Cerada et al., 3 and it is based on 90 pairs of cases in Lombardy in February, where the authors found an infector–infectee relationship and have the dates of symptom onset of both cases. Results are displayed in figure S8 in Cerada et al. 3 and refer to a Gamma‐distributed estimated serial interval with parameters shape = 1.87 and scale = 0.28. Bearing in mind that the Gamma is a continuous distribution and in this context is used to fit a discrete process, figure S8 in Cerada et al. 3 clearly shows multimodality and the Gamma distribution does not fit the data too well. In other words, the serial interval is poorly estimated. Moreover, this estimate is taken for granted for all the other Italian regions, that is, the same serial interval is assumed for all the regions and never updated. A crucial assumption for the adopted model is poorly estimated, wrongly applied to very heterogeneous contexts, and not checked again after the early phase of the first outbreak. We are puzzled about it, as the model by Cori et al. 2 accepts any parametric or empirical discrete distribution with support on positive values to approximate the serial interval and the generation time, and not only estimated values from a Gamma distribution. Gostic et al. 1 illustrate the consequences of misspecifying the form and the variance on the serial interval distribution. Moreover, Ganyani et al. 4 report country‐specific estimates for the generation time, remarking that estimating R t in different heterogeneous regions requires different estimates of the generation time. In addition, the delay between the date in which the result of the test was received and the date of the recording in the data set also plays a crucial role. Cori et al. 2 uses the instantaneous reproductive number and considers incidence cases observed before time point t; therefore, data may be affected by underreporting due to the delay between tests and reports: larger the delay, less accurate the estimation of R t due to missing information concerning incidence cases that are not yet recorded. Furthermore, the underreporting rate is not constant; it mostly affects the cases observed at the previous time points and closer to t, introducing a bias effect in the estimation. As a critical consequence, when the delay between test and report is large, the estimates of R t may be biased and in significant delay with respect to the current evolution of the epidemic process. Available epidemiological data are not ideal, and this reinforces, even more, the idea that statistical adjustments are needed to obtain accurate estimates of R t . As a result of neglecting all these issues, uncertain estimates of R t are obtained. Just to provide an example, we focus on the R t estimates reported in the ISS weekly report (see e.g., figure 8 at https://www.epicentro.iss.it/coronavirus/bollettino/Bollettino-sorveglianza-integrata-COVID-19_20-gennaio-2021.pdf). All credible intervals are rather wide, and even huge for some regions. The high uncertainty surrounding these estimates is a clear indication that the use of R t must be limited to provide a trend in the epidemic spread, but it must be avoided any further use. Annunziato and Asikainen 5 compare different methods to estimate Rt and show that point estimates vary across methods, though they share a similar trend. In Italy, instead, through a priori specified levels of the reproductive number, R t estimates are used to label the administrative regions in classes of risks (called scenario in the main ISS report, see e.g., http://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_monitoraggi_13_0_fileNazionale.pdf), with the respective restrictions. For estimating R t no golden standard methods exist. The work by Cori et al. 2 is a milestone in epidemiology research. Nevertheless, like many other models, it is based on assumptions that must be checked and fulfilled to avoid misleading inference. In Italy, not only are these assumptions neglected but the estimates of R t are used widely over their reliable interpretation. At the end of the games the R t seems a dancer, dancing music depending on the actual director of the orchestra who performs it.