- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Age Alone is not Adequate to Determine Health-care Resource Allocation During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Read this article at

Abstract

Background

The Canadian Geriatrics Society (CGS) fosters the health and well-being of older Canadians and older adults worldwide. Although severe COVID-19 illness and significant mortality occur across the lifespan, the fatality rate increases with age, especially for people over 65 years of age. The dichotomization of COVID-19 patients by age has been proposed as a way to decide who will receive intensive care admission when critical care unit beds or ventilators are limited. We provide perspectives and evidence why alternative approaches should be used.

Methods

Practitioners and researchers in geriatric medicine and gerontology have led in the development of alternative approaches to using chronological age as the sole criterion for allocating medical resources. Evidence and ethical based recommendations are provided.

Results

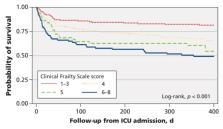

Age alone should not drive decisions for health-care resource allocation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Decisions on health-care resource allocation should take into consideration the preferences of the patient and their goals of care, as well as patient factors like the Clinical Frailty Scale score based on their status two weeks before the onset of symptoms.

Conclusions

Age alone does not accurately capture the variability of functional capacities and physiological reserve seen in older adults. A threshold of 5 or greater on the Clinical Frailty Scale is recommended if this scale is utilized in helping to decide on access to limited health-care resources such as admission to a critical care unit and/or intubation during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Related collections

Most cited references7

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

Association between frailty and short- and long-term outcomes among critically ill patients: a multicentre prospective cohort study.

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found